Quality over quantity: The importance of good bird seed

High quality bird seed sourced as locally as possible can make a significant difference in the number and variety of birds you are able to attract to your feeders.

A Goldfinch waits its turn to go to the finch feeder.

Buy locally grown for the best seed

Trying to save a buck when it comes to bird seed is not a wise decision… for a lot of reasons.

I found that out recently when I decided to pick up some cheap bird food at a local store known more for, let’s say, its car parts rather than bird food.

The specialty bird store I usually buy my seed from is in the next city over and involves a 20-minute drive, so I kept putting it off until it was too late and I needed to quickly restock my supply before a snowstorm hit.

A composite of a goldfinch and dark-eyed junco, the two birds that have taken to the new nyger seed.

The result is a large bag of bird seed that is maybe okay for the local squirrels and mice. (I’m actually putting the seed beneath our owl box hoping to attract mice to it to provide a ready-made food source for our little screech owl who lives in the yard.)

“Not only will a higher quality of seed attract more birds to your yard, it will attract a greater variety of birds.”

But, in searching the internet for a closer specialty store that stocks the seed cylinders I love so much, I discovered The Urban Nature Store – a Canadian-based bird and nature store that just happens to be located right in the small town where I live.

Turns out it’s been hiding just a couple kilometres away in plain sight for close to a year.

Why is this important? Because it verified what I already knew but choose to ignore to save a buck – high quality bird seed makes all the difference in the world. Not only high quality seed, but preferably seed that is locally sourced.

Not only will a higher quality of seed attract more birds to your yard, it will attract a greater variety of birds.

Let me explain.

On my first visit to The Urban Nature Store, I picked up a bag of nyger seed and a 25-pound bag of what they call their “no-mess blend” of bird seed.

My existing nyger seed was bringing in a grand total of zero gold finches, juncos or even sparrows, but within one day of filling the feeder with this new nyger seed, I had flocks of Juncos waiting in line to get their fill of this black gold. Today, I have a combination of juncos goldfinches and chipping sparrows lining up at the nyger feeder to get their fill of this important, high energy winter food source.

Cardinals, bluejays and a host of woodpeckers have reappeared in the yard since using a more locally sourced bird food.

There is a good reason why the old nyger proved unattractive to our backyard birds – it had simply dried out probably before I even brought it home. (For more on Nyger seed, go to my earlier post here.)

A few days after refilling the nyger feeders with this locally-purchased seed, I emptied our regular feeders at our main feeding station that was full of the cheap seed and replaced it with the no-mess blend seed from The Urban Nature Store. I also put one of the store’s seed cylinders up and within hours the feeding station was boiling over with birds lining up for a taste of this new seed. Cardinals, Blue Jays, Goldfinches, Dark eyed Juncos, mourning Doves, sparrows and a mix of woodpeckers including red-breasted and downy, just to name a few.

This was more bird action than I ever really got from even the best seed from my “other” specialized bird store in the next town over. This was truly remarkable.

The mess-mix is packaged in Canada using local and international ingredients, and combines sunflower hearts, peanut halves, dried cranberries and raisin. The mix is perfect for those who want to serve a variety of premium seeds with no messy leftovers. No shells means everything is eaten. The Nature Store reports that the seed mix is very popular with cardinals, chickadees, warblers and finches. Not sure about warblers, since they are primarily insect-eating birds.

And, since I have been using this seed, the number of birds at our feeding stations has only grown steadily.

Even the woodpeckers have returned with the new seed and seed cylinders from the Urban Nature Store.

“So what’s the difference?” you may ask.

Besides being a high-quality seed, an important difference is where it was sourced and the closer to home the better. This happens to be a Canadian-based store that sources much of its seed locally.

Who knows where big box stores source their seeds from, and I know that the other “specialized bird store” I purchased my seed from in the past was American based and likely sourced much of their seed from the U.S.

The closer you can purchase your seed, the more success you are likely to have. If you are based in the U.S., look for seed that was sourced nearby. The same holds true for U.K. based readers.

In the case of nyger seed, which mostly comes from Africa, the critical factors are how old the seed is and, if it has been overcooked in ovens that remove the natural oils that give the seed its nutrients. Purchasing from a specialized bird food store helps guarantee high turnover and is less likely to leave you buying old seed that has not been handled properly.

Not only has the seed from my local Nature Store been a magnet for local birds, the seed cylinder that I purchased is still going strong more than a week after mounting it, despite continued snow and rainfall that often prematurely weakens other seed cylinders I have used in the past. The fact it has held up so well means an extended run for the woodpeckers rather than the seed cylinder breaking up and falling to the ground for the squirrels and other critters.

If you have taken the time to check out The urban Nature Store link here, you will find that it is a wholly-owned and operated chain of Canadian stores with its head offices based in Toronto. It does offer mail-order for some products for anyone who does not live near one of its 9 store locations in

Ancaster/Hamilton

Etobicoke/Toronto West

Kingston

Markham

Mississauga

North York/Toronto East

Oshawa

Pickering

St. Catharines

I encourage all my readers to check out their impressive web site and support a truly Canadian company.

However, I recognize that we have many American and UK followers who cannot or choose not to purchase from The Canadian based Urban Nature Store.

All I am saying is that whenever possible – especially when it comes to purchasing bird seed – buy it from a local supplier. If the results I am having means anything, It really does make a difference.

Fresh bird seed that comes from a locally sourced supplier can make all the difference in the world to your bird feeding success.

Luminar Neo’s AI module shines as an educational assistant

Luminar Neo chooses to us Ai as a learning tool to help beginner photographers.

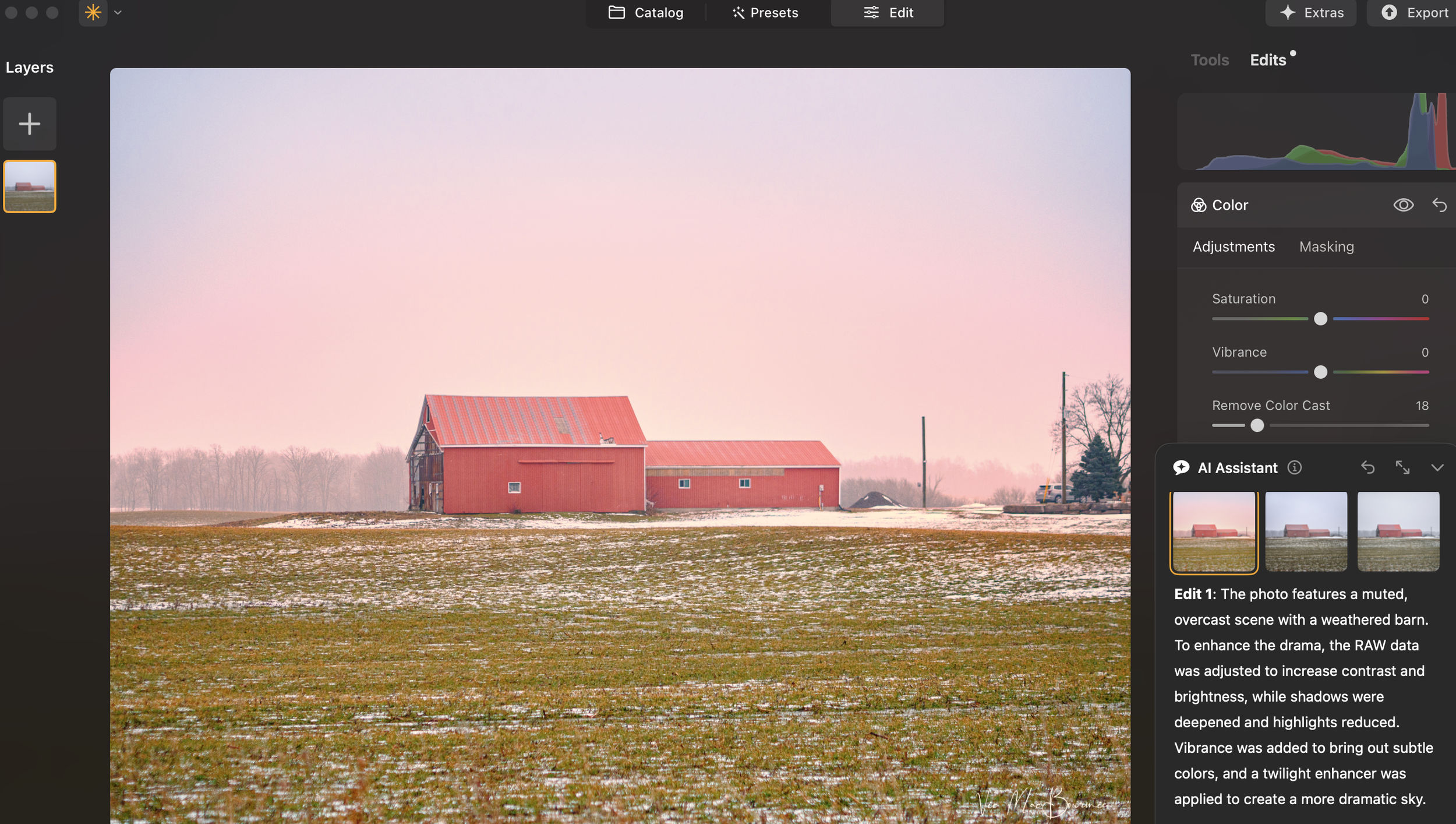

This image of red barns lit up dramatically against a stormy sky was created with a number of post processing modules. It’s important to note that the above image was NOT made with Luminar Neo’s new Ai module. In fact, an attempt to replicate it with the AI module proved fruitless. However, it’s equally important to know that the educational resources Luminar Neo’s new AI tool provides photographers – especially beginners – will help give them the knowledge they need to transform their images and create images like the one above from the original pictured below. The creators of Luminar Neo’s AI assistant believe that It is more valuable to know how to properly edit and create images than expect the computer to do all the work.

Using Ai as a learning tool

Whatever you think of Ai, there’s no denying that it is here to stay. The question many are asking is: Will AI be used for good, or for evil?

The answer to that question is still being written. Luminar Neo, however – unlike many other photo processing programs – is putting its support on the side of good.

The original image straight out of camera shows distracting elements, a bland sky and uninteresting lighting.

To be more precise, Luminar Neo is tapping into the power of AI to use it as more of an educational and learning tool, than one to dramatically manipulate images.

At least that is my initial impression after putting it to the test with a number of my images. The focus seems to be at least as much about education as it is about transforming images.

Understanding the capabilities of modern photo editing programs and techniques has never been more important.

After all, getting the most out of our images, whether they are from our latest vacation, pictures of our kids, grandchildren or flowers in our garden, is the goal for most of us.

The before and after pictures of the red barns are examples of how, with a little knowledge, we can transform boring images into dramatic ones simply by understanding a little about post processing techniques.

So how does Luminar Neo’s AI assistant help us achieve similar results?

The image below shows one of three suggested edits from the Luminar Neo AI assistant module. The image is much better than the original, but falls short in comparison to the full edited version at the top of the page.

Over time, however, we the AI assistant teaches us how to achieve desired results by explaining what tools were used and making suggestions on how the image can be improved.

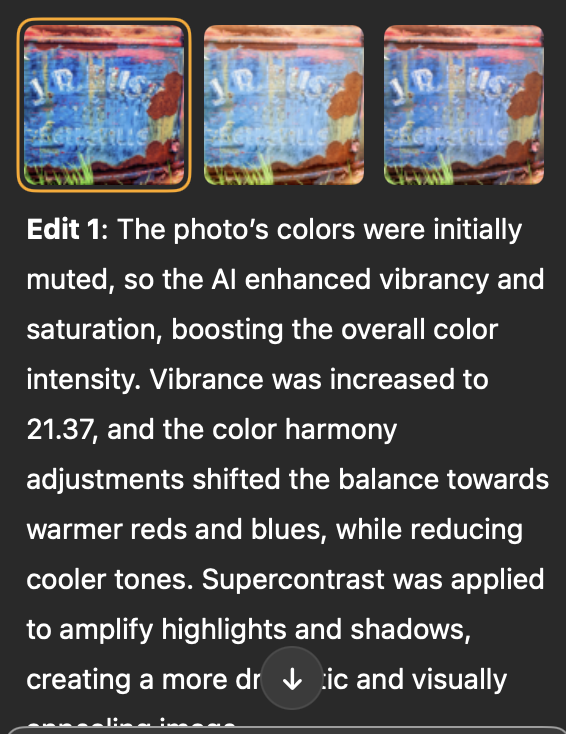

The above image is one of three suggestions Luminar Neo’s AI assistant suggested. You can see the suggestions and a detailed analysis of the above image in the Edit 1 description. You can also see that the suggested improvements are still rather subtle compared to the top image. Similar analysis are provided for Edit 2 and Edit 3.

How it works

Luminar Neo’s AI Assistant is available in both the Presets and Edit tabs and users can simply input text prompts to get AI Assistant’s editing suggestions.

There are two types of prompts.

Action prompts, like “Enhance this photo,” provide tailored recommendations with three adjustment sets and live previews, while How-to prompts, like “How do I remove this object?,” offer step-by-step guidance and buttons to quickly find the right tools in Luminar Neo.

It’s like having a personal editing advisor at your fingertips, helping you explore creative possibilities and discover the best tools and workflow for every image. You can use text commands in all Luminar Neo languages.

Back to our discussion about using AI in our work flow.

Knowledge about the tools available helped me create the top image. The original image’s sky was replaced and dramatic lighting was added in Luminar Neo’s Light Depth module.

“For the beginning photographer who has not yet perfected the art of post processing, this AI module is a tool that promises to transform their images over time and equip them with the knowledge they need to “make” outstanding images.”

In the past, we took pictures, today we make images

In photography, we often talk about “making” images rather than simply taking them. In the past, that most often was referring to “making” images in-camera during the analogue era of photography. Making images today with modern post processing can be taken a step further to include anything from minor enhancements to the photograph and removing distractions, to completely changing the image by adding elements not in the original image.

I’m not here to debate the validity of the different “levels” of enhancement, except to say that every photographer has to define the line they are not willing to cross. If you take a photojournalist approach to your photography, only minor enhancements are appropriate. If, however, photography is more a creative outlet for you, the same restrictions would not apply.

Important note: If you are looking to dramatically transform your images using ai, chances are you are not going to find those capabilities in this version of Luminar Neo’s AI module.

What you will find, however, is the ability to make positive, yet more subtle, changes to your images, while at the same time getting a thorough education on, not only what the program is doing to the image, but how the photographer can take control of the post processing and add their own creative effects using Luminar Neo’s wide range of creative modules.

For the beginning photographer who has not yet perfected the art of post processing, this Ai module is a tool that promises to transform their images over time and equip them with the knowledge they need to “make” outstanding images.

It might be the best use of Ai in any photographic post processing program. Understanding how to use post processing tools is much more important than just telling your computer to do the work. Luminar Neo does exactly that by adding three informative text-based explanations of changes it suggests for the particular image.

How to choose

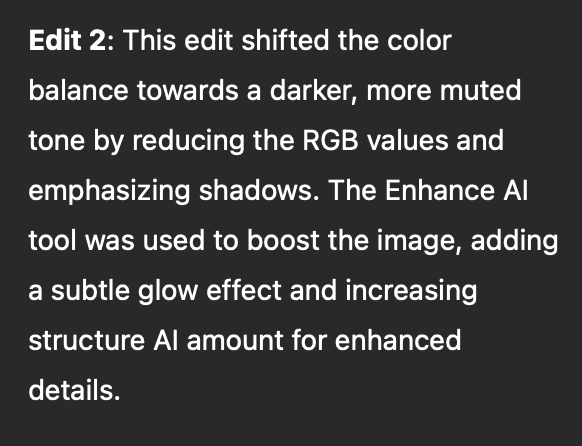

This image is the result of rather subtle changes made in Luminar Neo’s new ai module. See edit 2 for the list of enhancements added to the image by the ai module.

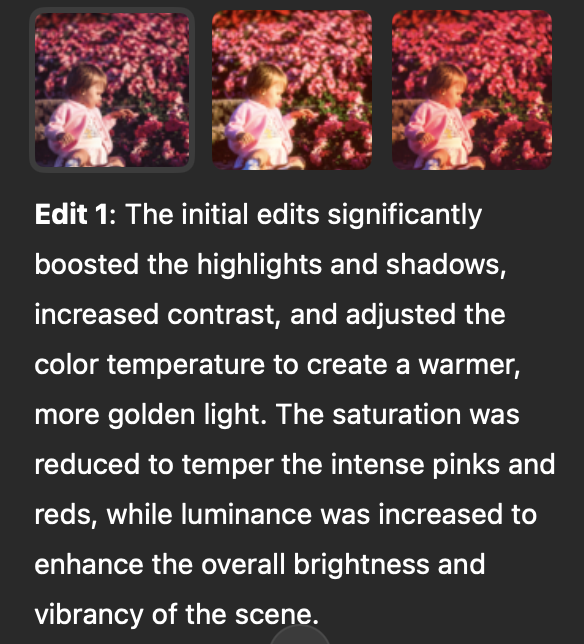

A good illustration is this image of a baby picking flowers at a local garden.

Once the Ai module is opened in Luminar Neo, the photographer is faced with two questions: 1) Typing in a command to enhance the image; or, asking the ai module how to use the tools available in Luminar Neo to make changes to the photograph.

The first suggested prompt is a simple one and a good starting point: “Enhance this image.”

If you choose this prompt, the program goes into action generating three different suggestions to enhance the image.

For this image the suggestions range from boosting the highlights and shadows and adding more golden light, to increasing depth of field and making colour harmony adjustments.

By explaining the enhancements, the beginner photographer gets an understanding of what is being done to improve the image and can take that knowledge to use with their other images.

Here the ai program responds to my request on how to get the best skin tones on the baby.

Other simple commands that are available to users include changing the photograph to a B&W image.

More important are commands to teach the user how to change the image. Questions such as: how do I remove distracting elements in the image, or how do I improve the skin tones in the image?

The result is a list of suggestions the program makes to guide the user to the appropriate modules to make the changes themselves. The result, a better understanding of the capabilities of the program and how to use it to make the images you originally envisioned.

Here is an original image of a rusty car before asking Luminar Neo to enhance the photograph. Below is the result after asking Luminar Neo’s AI to enhance the image.

The enhanced version of the rusting car and the explanation (below) of what was done to the photograph.

Luminar Neo is continually improving their Ai features and will certainly further refine many of the features in their recently released AI module.

Meanwhile, beginner photographers have a built-in assistant to help them learn the intricacies of the program and expand their post processing knowledge with the end goal of creating images anyone would be proud to share with friends and family.

If you are interested in further exploring Luminar Neo and its features, please use my link here.

Luminar Neo and Lensbaby combine for the ultimate in creativity

Adding a creative touch with Luminar Neo and Lensbaby lenses.

Our spring dogwood proved to be the ideal subject for the Lensbaby Composer and Sweet 50mm lens with a macro filter attached. Combine this soft, ethereal image with two subtle textures using Luminar Neo’s layering and blend modes and the existing photograph is turned into a painterly image that I’m betting most would be proud to call their own.

Textures add painterly effects to ethereal images

Ansel Adams once said you don’t “take a photograph, you make a photograph.”

Back then, Adams used the traditional darkroom to create magnificent Black and White images of the natural world, often times spending days in the darkroom “making” these images.

Today, the traditional darkroom has been replaced with the digital darkroom, turning the concept of “making” images rather than just “taking” them accessible to every photographer who chooses to explore their creativity and take their photography to new heights.

In this post, I am going to explore how, combining the inherent creativity built into every Lensbaby lens with the creative tools available in Luminar Neo, can change how you approach garden and flower photography as well as portraiture and landscapes.

• Go to the bottom of this post for the latest HOLIDAY offering from Luminar Neo

In case readers are unaware of the magical qualities of Luminar Neo post processing software and Lensbaby’s creative line of photographic lenses, let’s take a moment to familiarize ourselves with these creative photography tools.

While the first image of the dogwood flower is rather subtle, this image of paperbark maple leaves in fall shows what can be achieved with heavier textures applied through Luminar Neo’s layering and blending modules. The original image was taken with the Lensbaby 2.0 and sweet 50mm lens.

Luminar Neo is a photo editing software package that combines ease of use with the power of Ai to assist photographers, who may have been hesitant to dive into more complex photo editing software in the past, to embrace the ease and convenience of a more simplified, yet powerful, editing program.

Lensbaby is a lens manufacturer that embraces and encourages photographers to push creativity by offering lenses with unique characteristics that create elegant, soft-focus effects, beautiful colour blending and soft ethereal results that enhance almost any image, especially in the garden, with flowers and portraits.

In the final days leading up to Christmas, Luminar Neo is offering a special “creative” Advent Calendar package just in time for photographers to give themselves a special gift for the season.

The lowest price is available now, but once the doors officially open, the cost will range from $119 to $159 depending on if you are a new or existing user.

The Advent Calendar includes 12 unique surprises, each hidden behind a daily window. Photographers can discover a new gift every day, such as:

🔸 Luminar license

🔸 Marketplace items (Skies, bundles and more)

🔸 X-membership subscription

🔸 Educational courses

There are different surprises depending on the Luminar Neo package you choose or currently own.

Check out the information at the end of this post for details on the special creative and educational packages.

This image was taken with the Lensbaby Composer and sweet 50. It was then brought into Luminar Neo where a number of textures were applied creating a more painterly effect. One of the textures was also used to add the lovely, subtle pink tone to the image.

Adding textures to existing images is rather simple with Luminar Neo’s intuitive photo editing program. It’s as simple as dropping a textured image on top of your main image and then choosing from a host of blend modes from a drop-down menu. Once the texture is applies and the blend mode chosen, it is up to the photographer to decide if they want to go farther using masks or a host of other editing modules within Luminar Neo.

One of my new favourite modules is Luminar Neo’s incredible “Light Depth” module that is capable of transforming flat, boring images into beautifully lit, three-dimensional images. Check out my earlier post here, for more on using the Light Depth module in Luminar Neo.

These Northern Sea Oat grasses photographed with a Lensbaby 2.0 was given added interest by using a Luminar Neo built-in golden dust texture effect. You can create your own textures, find free ones on line or purchase more professional textures through Luminar Neo. Their latest creative package might just include some of their professionally produced creative tools.

If you are interested in exploring Lensbaby lenses further, you can check prices here (Amazon.com) or here (KEH used camera exchange.) If you are interested in exploring Lensbaby lenses further, check out the offering of books available through Alibris used books here.

My earlier posts on Luminar Neo

Adding textures, manipulating lighting, or even repairing old family photos are just a few of the incredible bonus features offered by Luminar Neo’s comprehensive editing software. For more of my posts on the benefits of exploring Luminar Neo, I encourage you to check out the following posts.

• Exploring Luminar Neo mobile for your phone: click here.

• Exploring Luminar’s incredible photo restoration module: Click here.

• Can Luminar Neo act as your only photo editing program. Click here

Subtle textures were added to this macro image of a Hydrangea blossom taken with the Lensbaby composer fitted with a Lensbaby macro filter.

Of course, garden flowers are not the only subject for Lensbaby lenses and Luminar Neo textured effects. Below is an image taken recently of our new flat Coated retreiver, Colby. This image was taken with the Lensbaby Velvet 56. The Velvet series of lenses are capable of truly beautiful results with an ethereal glow that is magnified depending on the f-stop used (from quite sharp at f5.6 through f16 and getting softer from F5.6 through to F2.

Two B&W textures were added to the original image to maintain the overall B&W, painterly effect.

The image below and the above images represent just a few of the creative approaches available to photographers using special effect lenses and/or filters, and combining them with the creative effects available through Luminar Neo. Please explore the links provided for my earlier posts on Luminar Neo and be sure to click below to check out all of the special deals on creative assets, tools and educational resource materials Luminar Neo is adding for their “creative advent calendar.”

Our rescue Flat-Coated Retriever with his baseball stuffy taken with the Lensbaby Velvet 56 with two textures added for a painterly effect.

Luminar Neo’s holiday calendar of gifts explained

From December 13th to 24th, open a new surprise every day and discover creative tools, content, and inspiration worth more than $1000.

The calendar can also be gifted to friends, family, or photography enthusiasts, making it a thoughtful and creative holiday present.

Here’s what all the excitement is about. Unlock your treats every day leading up to the big day.

Calendar Timeline:

December 10: Presale begins with lower prices

December 13–24: Daily windows open (one per day)

December 16–25: Calendar available at full price

Luminar Neo brings treasured family memories back to life

Restoring vintage family photos has never been easier with Luminar Neo’s new Ai restoration module.

Luminar Neo not only took this outstanding vintage black and white image of my mother, father and aunts posing with our cousin Audrey and her husband, acclaimed singer of the Ink Spots, Bill Kenny, but modernized it with an extraordinary colour rendition using the “Full” module in the post processing photo program. (see BW image below.)

Restoring, colourizing vintage photos

Not long ago, fixing old family photographs involved bringing them to professional photo retouchers and paying a week’s salary to have a handful of them restored.

Those days are gone thanks to a new, incredibly impressive new feature in this fall’s Luminar Neo release.

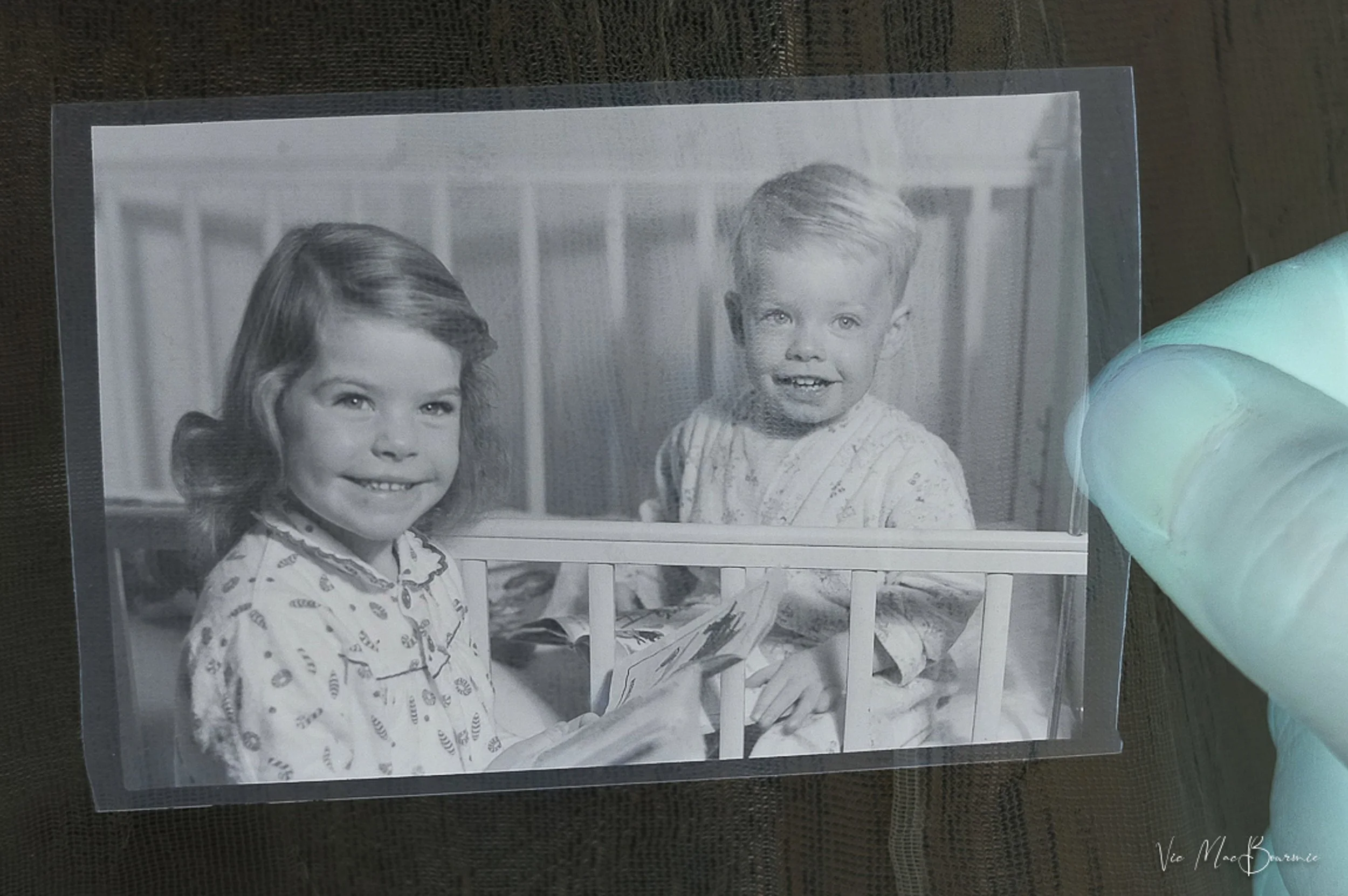

With a single click of your mouse, you can transform a faded, scratched, blemished old black and white photograph into a perfect reproduction of the original Black and White version.

And that is just the beginning.

The simplicity of the “restore” module is almost too good to believe.

Rediscover treasured photos

This prized family group portrait of the acclaimed lead singer for the Ink Spots Bill Kenny and wife Aubrey pictured here with my mother (2nd left and father far right) at a club in Halifax Nova Scotia. Luminar Neo was able to repair any scratches and blemishes on this BW image with the simple click of a single button. Another button colourized it (see above).

Restore module is the essence of simplicity

In fact, there are just three buttons to choose from to transform your vintage images: “Full” which repairs scratches, blemishes and colourizes the image to modern standards; “Colour” which simply colourizes the image without removing scratches and blemishes for a more authentic Lomography look; and “Scratches” which leaves the image either in its original BW or colour state and simply removes any scratches or blemishes on the photograph.

It’s so simple and effective that it is difficult for me to go into much more detail than – choose what you want to do and press the appropriate button.

If you are interested in trying Luminar Neo, please consider using my affiliate link HERE to purchase the program. By doing so, I receive a small payout that does not affect your purchase price.

This is the restoration module in Lumina Neo. Simply drop the image into the box and choose Full, Color of Scratches. Then hit the Restore button. The final image will show up in a separate folder within Luminar Neo called “Restoration.”

My sister and I on large format negative inverted.

The same image of my sister and I ran through the full module which colourized the photograph as well as adding some interesting vintage touches. Running the images through the module can result in slightly different results, which makes the entire process even more exciting to see the results.

Obviously, you will have to have a way to get the old images into Luminar Neo. I choose to use a flatbed scanner, but you could easily take digital pictures with your phone or, even better, a digital camera with the ability to take close-up images.

Once the images are on your computer or phone, import them into Luminar Neo, drop them into the restoration box, choose the appropriate button – either Full, Colour or Scratches – and Luminar Neo will drop the finished photo into a separate folder named restoration.

It’s as simple as that. The following are just a few examples’s of what the “restoration” Ai module can do in just a minute or two.

For more before-and-after images, check out my new “Spaces” gallery from Luminar Neo here.

The original BW image prior to any post processing.

A “Full” colorized version of the vintage image.

The following is a good example of what the Luminar Neo “Restoration” module can do for heavily compromised images by not only restoring them by removing scratches and even missing parts of the image, to colourizing them to create authentic-looking images.

The following shows the original scan, a repaired scan and the final colourized version.

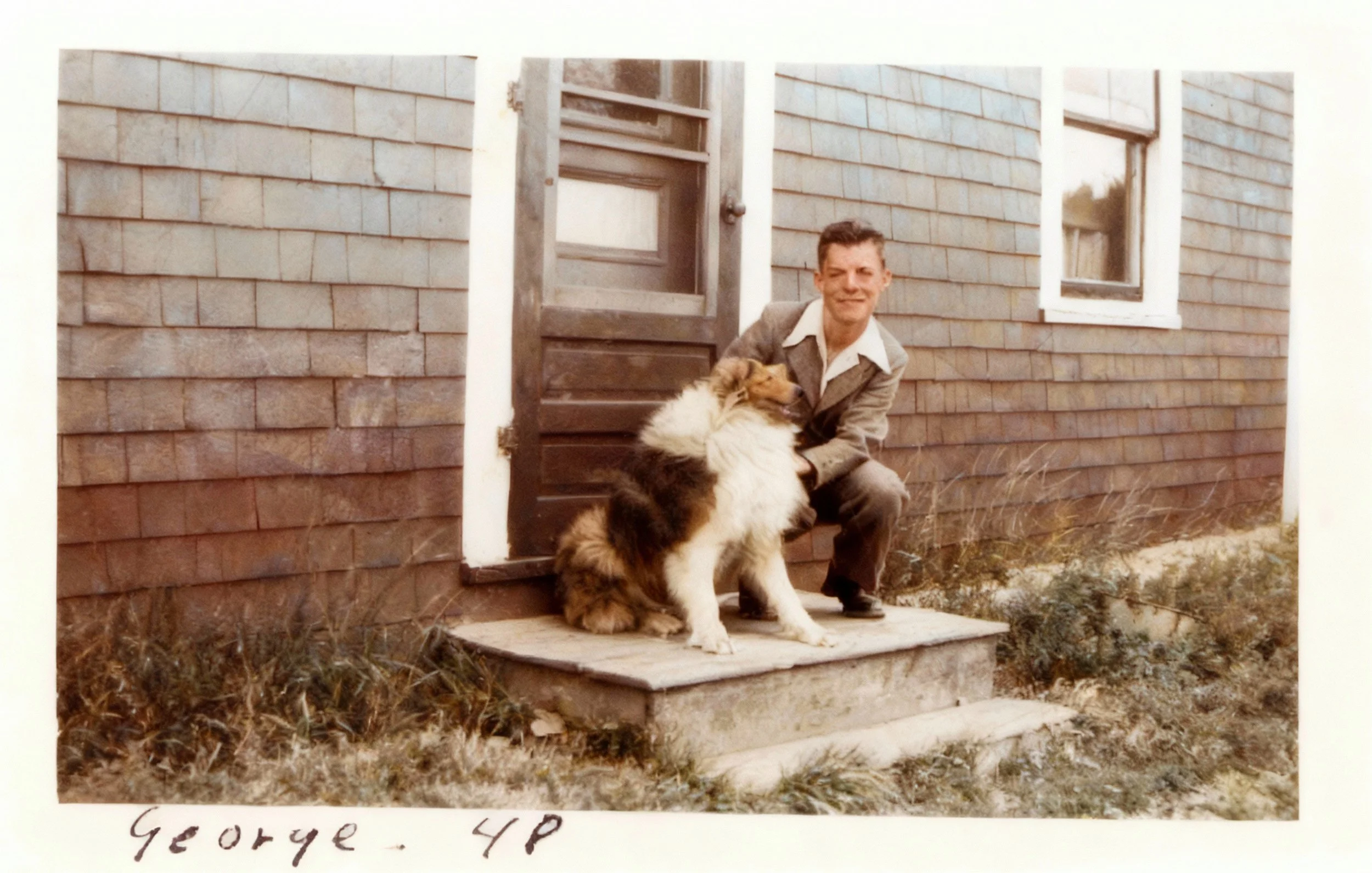

This is the original, untouched image of my uncle and his dog.

The same image ran through the restore module – a single click of a button in Luminar Neo.

The final restored and colourized image. Note that the ai changed the dog’s profile slightly.

If you are interested in trying Luminar Neo, please consider using my affiliate link HERE to purchase the program. By doing so, I receive a small payout that does not affect your purchase price.

If you are a new user to Luminar Neo, use this link.

If you are a current user of the program, use this link

Prices below: Black Friday is Coming:

Dates: October 24 - December 1

Discounts: Up to -75% on the Luminar Neo Ecosystem - the best prices of the year!

Prices for new uses:

Luminar Neo Desktop Perpetual: $99

Luminar Neo Cross-device Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile): $139

Luminar Neo Max Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile + Spaces): $159

Luminar Neo takes lighting to another level

Luminar Neo has changed the way we see light forever.

This woodland fall scene is an example of how Luminar Neo’s new light-depth module can transform a relatively flat image into a more three-dimensional one. The smaller inset photo below shows the original image.

Transform your fall images with newest tool

If photography is all about light, Luminar Neo may have just rewrote the future of post processing.

I can’t think of a single feature, besides Ai erase and replacement, that has excited me quite as much as Luminar’s new Light Depth module.

Subtle but sweet

The change in the photos is subtle unless you know where to look. The light in the first image is moved forward to create a strong foreground band of light that lights up the brush in the front as well as the tree trunks. The effect helps to give the entire image added depth.

This module can take a good image to greatness in seconds and create a completely controllable, three-dimensional-lighting effect that is unmatched by any other post processing program I have experienced.

And, if used carefully, it can be beautifully subtle, or, not so subtle at all but always believable.

It’s just one of the new features unleashed in Luminar Neo’s fall package that includes a host of outstanding additions from improved mobile/desktop compatibility, to a highly useful photo restoration module that also has the potential of changing the way photo restoration is done both for amateur and professional photographers. And all of this added to an already impressive package of features for a very low price. For pricing details, go to the end of this post.

For more of my images showing Luminar Neo’s new Light Depth module as well as their free galleries for members, click here.

Although the Beech tree was also “lit up” in the original image, by manipulating the light depth module settings, I was able to darken the background and create a much more dramatic image. In addition, I used Luminar Neo’s light ray module to emphasize sunrays coming in from the right side of the frame.

If these three additions were not enough to convince anyone sitting on the fence about diving into this Ukraine-based post-processing photography package, this extremely innovative company is adding personal galleries to their repertoire of features to allow Luminar Neo users to share their best work with family, friends, clients and other Luminar Neo users.

I’ll be making separate posts on these features in the future.

If you are interested in trying Luminar Neo, please consider using my affiliate link HERE to purchase the program. By doing so, I receive a small payout that does not affect your purchase price.

Added drama

The before-and-after shows the dramatic difference created by darkening the background by shifting the light in the depth module. Luminar Neo’s new feature helps to create a more three-dimensional look.

Luminar Neo Light Depth module: Painting with light

But back to the reason for this post: The incredible “Light Depth” module.

I am not going to try to explain how this thing works, but suffice it to say that it’s an example of how ai can transform your images in subtle, yet incredibly useful ways. The module does not add anything to your image, it simply helps the photographer to manipulate the lighting in the scene.

How it all works in real life

In short, the module allows you to control the light “near” the front of the image, and the light toward the back of the image. Sliders give the photographer control of the amount of light, the warmth of the light and the softness all the while providing a map of the scene to help the user control the light in quite fine detail.

The module’s secret sauce can transform your images from flat, evenly lit scenes into more three-dimensional images with much more depth.

Below are a few before-and-after images I took just recently of fall colours in the woodland around our home showing the results. I try to keep most of the edits subtle, but you can choose the amount and quality of light you feel is needed to create the images you are trying to achieve.

This spectacular old oak tree set against the colours of fall literally stopped me in my tracks. Pulling the oak tree away from the background proved to be relatively simple in Luminar Neo’s Light depth module. without it, the scene (see below) is rather flat and the beautiful oak tree dissolves somewhat into the overall scene.

The rather flat lighting seen here, does not put the beautiful old oak tree in its best light.

Although I loved the birch trees and the leaf-covered pathway in this image, the lighting in the original proved to be very flat. Luminar Neo’s Light Depth module created the ray of light across the pathway and into the tree canopy as well as adding a subtle light to the birch trees. The result is a more three-dimensional image with a whole lot more interest. This result probably could have been achieved with other post processing software, but certainly not this easily and with this amount of control.

Adding depth to flat lighting

The before picture is rather flat in comparison to the edited version. Of particular note is the absence of the ray of light that cuts across the leaf-covered pathway in the edited version,.

Luminar Neo’s new tool will help transform your fall images

Fall is a spectacular time to get out and capture the rich colours all around us. However, no matter how good the colour is, lighting plays an important role in the success of your images. Getting out at different times of the day including early morning and late afternoon improves our chances of capturing great light, but there are no guarantees.

Luminar Neo’s new Light Depth module helps photographers improve their chances of creating images with interesting light by giving them control of the light in post processing. The results can be subtle, yet very effective.

If you are interested in more of my posts on using Luminar Neo, check out the following links:

• Luminar Neo in the woodland.

Fall colour and birch trees using Luminar Neo’s Light Depth feature.

If you want to see more of my fall images using Luminar Neo’s Light Depth module, be sure to check out my new Fall 2025 Gallery brought to you by Luminar Neo as part of their fall rollout of features. Check it out here.

If you are considering adding Luminar Neo to your existing photo processing packages such as Lightroom and Photoshop, it should be noted that the programs work seamlessly together. You can even open Luminar Neo from within Lightroom.

If you are wondering about the cost of this exceptional photo editing program, let me share some information and a couple of images that might help convince you to make the jump.

This image taken with a Lensbaby and the Light Depth module creates an interesting effect that I think works nicely.

If you are interested in trying Luminar Neo, please consider using my affiliate link HERE to purchase the program. By doing so, I receive a small payout that does not affect your purchase price.

If you are a new user to Luminar Neo, use this link.

If you are a current user of the program, use this link

Prices below: Black Friday is Coming:

Dates: October 24 - December 1

Discounts: Up to -75% on the Luminar Neo Ecosystem - the best prices of the year!

Prices for new uses:

Luminar Neo Desktop Perpetual: $99

Luminar Neo Cross-device Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile): $139

Luminar Neo Max Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile + Spaces): $159

Prices for existing users of Luminar Neo:

Ecosystem Pass: $69

Upgrade Pass: $49

Prices for legacy users of previous Luminar versions:

Luminar Neo Cross-device Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile): $89

Luminar Neo Max Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile + Spaces): $109

Why I chose the Pentax Q7 to capture a European river cruise vacation

Is the Pentax Q system the ultimate travel camera? Decide for yourself after checking out the results on our European river cruise.

Convenience, quality wrapped in a tiny package makes Pentax Q series the perfect travel cameras

Okay, before you start laughing, let me explain.

Yeah, the miniature 20-plus-year-old, Q7 mirrorless camera with its tiny 12.3 megabyte 1.17-inch backlit CMOS sensor would not be many photographers first choice to document a once-in-a-lifetime family Rhine river cruise vacation.

In fact, I’d bet I’m probably standing pretty much alone here, with maybe the exception of all but the most die-hard Pentax Q users.

And that’s fine with me.

Pentax Q: Tiny and terrific

The Pentax Q with its fine collection of proprietary lenses, just might be the best travel companion for those simply looking to document their vacation with a high-quality camera and lenses that is small enough to fit into a coat pocket.

The purpose of the vacation was not to capture incredible images, rather it was to spend time with my wife and adult daughter. In other words, I felt the experience was going to be more important than the images I was going to make on the vacation. Afterall, time limitations and tourists getting in the way makes serious photography difficult on these types of vacations, to say the least.

Complete system fit nicely in a coat pocket

I figured the Pentax Q system was, at least, better than relying on my phone for capturing memorable moments, and, being able to fit the miniature camera and all three lenses into a coat pocket would allow me to grab the odd shot without having to lug around a full system of cameras and lenses. I’ve made that mistake too many times in the past and was determined not to make it on this vacation.

So, after much thought prior to the trip, I convinced myself that, because of the limiting factors of time and an abundance of tourists, at best I was going to get a couple of nice snapshots.

Boy, was I wrong and more than a bit surprised..

But more on that later. Let’s continue this talk about the interesting camera decision.

For more on the Pentax Q system, check out my other posts below:

The tiny Pentax Q7 fit nicely in my coat pocket and could be easily retrieved at a moment’s notice to capture an iconic scene like this one of a man walking down a deserted street in the heart of a quaint German town. (Pentax Q7, ISO 1600, 1/125 sec, F5, with 02 standard zoom at 14.9mm.)

Sigma DP2, Fujifilm X10, Olympus and Lumix micro 4/3 cameras all stayed home

My camera choice certainly wasn’t because the Q10 and accompanying lenses were the best I had available to me. I’ve got Olympus and Lumix M4/3 systems, A Pentax APS K5 system, the venerable Fujifilm X10, the Lumix LX7, even a Sigma DP2 as well as a host of other cameras to choose from. (I know I have a problem.)

But when it came down to it, I chose the Q7 along with the 50mm (01) equivalent, 28-80mm (02)kit zoom and the weird little fisheye lens. I meant to take the 80-200mm equivalent (06) to give me some pull-in power, but in my haste to pack everything, I grabbed a second 28-80mm kit lens instead.

I should say that I also packed a Fujifilm EXF660ER travel camera with a 16mp CMOS sensor and 24-360mm zoom lens, which I had purchased a few weeks earlier from a thrift store for $12 Canadian. Its 360mm reach easily took the place of the 80-200mm 06 lens for capturing distant scenes. However, the Fujifilm was used only sparingly and often when the Q10 battery died while out on the town.

Would I do it again? In a heartbeat.

But, rather than explain my decision and trying to justify it to an audience that can’t imagine bring the tiny Pentax instead of a larger format system, let me show you why.

I think these images speak for themselves.

Montreau, Switzerland taken with the Pentax Q7 from the Lake Geneva boat cruise. (Pentax Q7, ISO 100, at 320 sec at 9.1mm.

From past experience, I knew the Pentax Q system was capable of capturing exceptional images. Despite the tiny sensor, the camera boasts the ability to shoot both high-quality JPEGs as well as RAW (DNG) files, has very capable image stabilization built into the camera and no anti-aliasing filter to soften the image. I believe the lack of anti-aliasing filter is often overlooked by many, but accounts for the very sharp images achievable straight out of camera.

The results point to a surprisingly capable camera system more than up to the task of capturing extremely sharp images with the array of dedicated lenses. This is not even taking into consideration the huge number of third-party lenses that can easily be added to the system from the diminutive 110 lenses (see story here) to a host of manual lenses via a simple adapter. (seee story here)

Before the trip, I added a step-up ring which, in turn, allowed me to use a polarizing filter to deepen the blues in sunny skies and remove unwanted reflections from water, windows and other reflective surfaces.

After going through almost 2,000 images, I think I can safely say that I was not disappointed. In fact, once again, this little camera system managed to impress me even more than I expected.

I was careful to photograph everything in both Jpeg and RAW formats and, although the JPEGs were more than useable, I chose, in most instances, to work with the RAW images in Lightroom to pull out fine detail and a wider exposure range. The RAW DNG files proved to be incredibly easy to manipulate and arrive at the results I was wanting to achieve.

To my surprise the kit zoom (02) that gives a zoom ratio of approximately (28-80 range) with the Q10, was used for maybe 80-90 per cent of the images. Most of the images included the polarizing filter, if nothing else to cut glare.

Eight dedicated lenses to choose from

For a little background, Pentax introduced a total of 8 miniaturized lenses beginning with the excellent 01 standard Prime with a focal length of 8.5 mm (47mm equivalent for the Q, Q10, and 39mm for the Q7, Q-S1 with the larger sensors.) More lenses followed: 02 standard zoom (27-80 range equivalency, 23-69mm), 03 Fisheye (17.5mm, 16.5mm), 04 Toy wide angle lens ( 35mm, 33mm), 05 Toy lens (100mm, 94mm), 06 Telephoto zoom (83-249mm, 69-207mm), 07 Shield mount lens (63mm, 53mm) and finally the 08 Wide Zoom (21-32mm, 17.5-27mm). For more complete story on the hard-to-find O8 wide angle lens click here.

The lake cruisers traditional looks and almost silent motors made the Lake Geneva cruise a real joy. (Pentax Q7, ISO 200, 02 lens at f4 and 5.5mm.)

One of the weaknesses of the Q system is their tiny batteries which do not hold the best charges. I carried two batteries most days, but was able to get through the majority of days with a single battery by conserving the power by turning off the camera immediately after using it and keeping chimping (checking the images on the back LCD screen) to a minimum.

Keeping an eye out for interesting “street” images adds more depth to your typical vacation photographs and helps to capture a greater sense of the local character.

Ideal system for capturing street scenes

As a former journalist, capturing interesting street scenes was a prime focus whenever I was wandering the small towns and cities where the river cruise ship stopped. Nothing screams professional more than a large 35mm camera and an array of lenses cascading out of the camera bag. That’s not the image I wanted to convey while wandering the back streets trying to capture street scenes.

A couple strolls down the quintessential European street in the heart of a quaint German town (Heidelberg I believe). (Pentax Q7, ISO 400, F4, with 02 standard zoom at 11.2mm.)

Nothing could be more inconspicuous than the miniaturized Pentax Q system. Even with the 80-200mm f2.8 mounted on the camera, no one is going to mistake you for anything more than an annoying tourist, if they even notice you are photographing them at all. The whole package is so small that, if you are shooting from the hip, I can guarantee no-one will take notice.

This well-dressed woman seemed to be taking a moment to do a little people watching or maybe waiting for a friend, but I could not resist capturing this captivating scene.

These are just a few “street scene” images taken during our two weeks in Europe. I hope to write a separate post on capturing more authentic images on vacation rather than just your family members posing in front of typical tourist destinations, which will include capturing street scenes.

Getting a grip on the Sigma DP series cameras

The incredible Sigma DP series of cameras with their minimalist approach to design combined with an outstanding foveon sensor makes them a true cult camera. Adding a third-party 3-D printed grip only makes the cameras even better.

Third-party grip takes street photography to a new level

Let’s start by saying I love the minimalism of the Sigma DP1 and DP2. Their simplicity, along with their incredible foveon sensors give them special status among the many high-end point-and-shoot cameras in my arsenal.

My Sigma DP2’s brick-like look and feel is perfect when I’m using it out of a camera bag or from a tripod capturing landscapes in the woodland. However, when it comes to street photography, I like a good grip to give me the assurance I’m not going to accidentally drop one of my favourite cameras.

That’s when Shutterspeedblog’s creative expertise comes into play with its outstanding grips for the Sigma cameras as well as a host of other high-end cameras from Leica, Canon and Lumix just to name a few.

Sigma Hand grip

The 3-D printed grip has been meticulously designed to incorporate both a grip and thumb rest, while allowing access to the battery and SD card.

There is something comforting about walking around town with the Sigma DP2 hanging off your fingertips ready to capture anything that catches your fancy. Of course, I use a simple wrist strap for a little added insurance, but the camera sits nicely in my hand with just the grip. The built-in thumb rest is added security and helps me to hold the non-ibis camera still during longer exposures.

Grip and build-in thumb rest

This overhead view shows the grip and build-in thumb rest that helps to make street photography style shooting with eh Sigmas that much easier.

The meticulously 3D printed grip also allows access to the battery (and we all know how important that is for the battery-eating Sigmas) and SD card, to make the entire experience seamless.

Want to remove the grip? Unscrew it from the tripod mount. Want to still use the camera on a tripod? No problem, there is a separate, yet very sturdy tripod mount built into the grip.

There is no doubt that the very reasonably priced grip significantly improves the handling of the camera. Depending on the size of your hands, some of the buttons on the back of the camera might be a little more difficult to reach, but that is a miniscule price to pay for the convenience the grip provides.

Lumix LX7 grip

Similar grips are made for Lumix, Leica, Canon and other high end point and shoot cameras.

I decided to give it a good workout during a walk with our new dog down the Main Street of our small town. Walking a dog and carrying a camera loosely in your hand is not always recommended, but the new grip on the Sigma made it not only possible, but immensely enjoyable. All I had to do is raise the camera and shoot away like a real veteran street-shooter.

I can only imagine how much easier it will be to use the grip on the cameras for someone who regularly shoots from the hip, whether they are using the camera in manual focus mode or autofocus.

The following are just a few more images from my morning walk with our Flat-coated retriever, Colby and the Sigma DP2 and grip from Shutterspeedblog’s eBay store.

Colby goes to church

A quick grab shot of Colby in front of a gothic church door. The grip just makes stealing images like this much easier with the Sigma series of cameras.

Luminar Neo to the rescue

Let’s put Luminar Neo post processing software to work to try to rescue a roll of long-expired film.

Trying to save terrible negatives from long-expired film

It was a dumb mistake. In my hurry to test out a new film camera I had received, I failed to check the film I had loaded in it and went off to run a test roll through it to ensure the camera was working properly.

Turns out the roll of “Black’s Camera film” was likely at least 10 years old and stored inside the camera (not a good idea unless the camera was in a fridge for 10 years. I had not set the camera for any compensation for outdated film (Not that I could easily over ride the ASA setting with this point and shoot camera anyway.)

It wasn’t until I pulled the finished roll of film out of the camera that I realized this was likely long expired film that was given to me along with the camera.

I could have asked the lab to push the film a stop or two, but decided to ‘let it ride,’ as they say.

The results were far from perfect. In fact, they were downright awful. Still, I hoped, salvageable with a little (well maybe more than a little) work in post processing.

So, I decided to put my newest post processing software, Luminar Neo, to the test.

This is the same image as the one pictured above before and post processing was applied.

Let’s just say it would have its work cut out for it trying to rescue this old outdated film.

The negatives had a dark, almost eerie appearance to them that looked like they had been run through a bath of black ink. They were dark and murky and just plain ugly. A few were completely unreadable, but most had enough of an image to make scanning them on the Epson flatbed a worthwhile endeavour.

These were originally taken as test images, so there was nothing I couldn’t live without. They were mostly early spring garden images.

If they were priceless family pictures, I would have taken more time with them in post processing and probably would have been able to squeeze out a little better results. Given that they were simply test images, I wasn’t prepared to spend a lot of time trying to rescue these image. With that said, it’s probably wise not to expect miracles.

The lesson I’m hoping to provide readers is that, even if you have very old, faded or extremely underexposed images, there is still hope, especially if you are willing to put in the time to rescue them from the trash bin. These are not images you want to put up on social media, but if they are historical family documents, they would probably be worth rescuing and might even become cherished family keepsakes.

Below are a few of the before-and-after results after running the negatives through Luminar Neo’s comprehensive post processing modules.

It’s difficult to explain everything I did to try and rescue these images. Each image was treated separately and needed varying degrees of editing.

One editing module that I did find extremely helpful was a feature in the Creative Module called “Color Transfer".” This module is rather unique and lets the editor choose an existing photo (either one of the provided ones or one of his/her own) and “transfer” the colours from that image into the image being edited.

This technique – using one of my own garden images – helped me retrieve many of the original greens in the expired images.

The results vary considerably and it’s safe to say that these are not social-media-worthy images. But, as I said, if you have severely degraded negatives that are important to you, there are ways of rescuing them to a respectable level.

Or, maybe it’s best that you be the judge. Before-and-after images below.

All of these images were post processed using the Ukraine-based Luminar Neo. I have partnered with the company and can offer readers a 10 per cent discount at checkout with my code “FernsFeathers.” Using the code will not cost you anything, but I get a small amount of money to keep me writing articles like this one.

If you are interested in exploring Luminar Neo further, check out my posts here (Luminar Neo in the woodland garden and nature) and here (Is Luminar Neo the only software I will need) and here (exploring a film camera and Luninar Leo)

Happy shooting.

In this image I tried to bring back some of the original greens in the image and bring up some of the clarity in the image by removing the veil over the original image below.

Original image SOOC prior to post processing

Another successfully rescued image thanks to the post processing power of Luminar Neo

Garden image of yellow irises prior to post processing by Luminar Neo.

I probably should have given up with this image shot on expired film, but I was determined to get the most out of it. Here is the result. While it looks pretty bad, it’s a massive improvement from the original image SOOC pictured below.

This image SOOC shows the extreme degradation of the long-expired film. Although the above corrected image is far from stellar, if it were a cherished family picture, it would at least be a major improvement.

Minolta 125 film camera: A classic point-and-shoot

The Minolta 125, point-and-shoot, 35mm film camera is ideal for a new photographer or one interested in experimenting with Lomography.

Beginner photographers and Lomography aficionados will love this little gem

This post is a combination of a review of the Minolta 125 film camera as well as a focus on post-processing using Lightroom and Luminar Neo. I hope the post illustrates the importance of post processing your images, whether they are from a digital camera or a film camera. Learning this skill does not have to be difficult. Luminar Neo developers have gone to great lengths to simplify the process so that excellent results are more easily achievable. Please take a moment to check out my other posts on Luminar Neo listed at the end of this post.

If you’re looking for a 35mm film camera that just works with little to no fuss, this little compact Minolta might fit the bill.

Forget about setting it on manual, adjusting apertures or shutter speeds, this is a genuine point-and-shoot camera from the year 2000.

It has a lovely high-quality look to it with a champagne and silver exterior combination that might make you think it’s a very high quality all-metal Contax or Rollei. Pick it up, however, and you’ll know it’s not in that league. It does appear to have an all-aluminum front and bottom plate, but high-quality plastic abounds in the back and in other parts on the camera.

Before and After

Image shows the Before-and-after following some work in Luminar Neo. Notice how the colours, especially the greens and magentas pop in the Luminar Neo image at right.

Mind you, the Minolta Riva Zoom 125 is a fine example of an autofocus, DX-coded, film point-and-shoot camera that can deliver very pleasing results without a lot of thought on your part. It will read film from ISO 25 (think Kodachrome) to 3200 but the recommended film is ISO400. In my tests, I shot ISO 200 for a finer grain, and used a tripod to reduce the chances of motion blur.

Before and After image

This shows the before-and-after image. The photograph on the left is the Lightroom image and the image on the right is after additional post processing with Luminar Neo, including a complete sky replacement.

How it performs

Would it be the only camera I would take on an important shoot? Absolutely not. But, for a very lightweight, simple camera that can fit in a pocket, it’s certainly one that most film shooters would be happy to carry around as a back-up, or one to take with them to grab shots at a party or fun family event.

For students of Lomography, this little Minolta will allow you to focus on getting the images rather than the technical aspects of photography.

A highly competent flash (with red-eye reduction and a fill-flash feature), and superior lens doesn’t hurt either.

What sets the Minolta apart from many point-and-shoot cameras is that sweet Minolta lens that starts at a convenient wide angle range of 37.5mm and stretches to 125mm.

This little Minolta has a nice finish, a great lens and easily fits in your pocket.

Not particularly fast at f4.5 -f10.3, but the built-in flash comes in handy to stop motion and a tripod with the electronic self timer can be used if you are working a landscape. For those who care, the lens is a 6 elements/ 6 group construction with a close-focusing capability of about 2 feet.

Minolta added an ingenious electronic zoom lever that is actually set up to give the user access to the most poplular focal lengths – five to be exact. At the widest end you are at the 37mm focal length – consider it a sweet little 35mm. One click and you are in the 50mm focal length. Hit it again and you’re at the perfect portrait setting 85-100. One more click and the lens zooms to its max at about 125 – close enough to the popular 135mm focal length.

Buy these lenses separately, and you’ll be paying 10 times the cost you could probably pick up one of these on the used market these days.

An orange flashing LED on the viewfinder provides several warnings from; flash will fire, flash charging, and camera-shake warning, depending on the blinking speed. Above the orange light is a green light that tells the shooter the subject is in focus, subject is too close or the contrast is too low for accurate focusing.

Stream and waterfalls

Extensive post-processing was to rescue this image, including removing unwanted objects, adding an Orton-effect to some of the foliage and boosting the blues and greens in the stream and waterfalls to give it a more pleasing colour.

Before editing

This image has had only minor edits to it in Lightroom. The above image shows the results after work in Luminar Neo post processing software.

The flash can be set to auto flash, auto flash with red eye reduction, fill-flash, flash cancel, and night portrait (with red-eye reduction.)

For my woodland garden, landscape and flower test shots, I set the camera on automatic, turned off the flash and popped the camera on a tripod. To ensure the sharpest images possible, I also used the built-in self timer with ASA 200 Kodak film.

For close-focus subjects, lines engraved in the viewfinder corrects parallax issues and helps the user get the image they were hoping to capture. That’s a nice touch for flower photographers looking to capture subjects without a lot of complex macro gear.

It takes a relatively inexpensive single CR123A lithium battery that can handle about 12 rolls of 24 exposure rolls with flash for 50 per cent of the exposures.

Four small buttons on the top control the on/off, flash, timer and date functions. (some cameras including the one I used do not have the date button.)

An LED screen on the top plate provides the needed information including battery life and film counter as well as the camera’s other settings – flash, timer etc.

Important notes: Minolta made it difficult to accidentally open the camera back before the film is rewound. That’s a good thing. The back locks until the film is rewound into the spool. It can be over ridden if you want to change film mid-roll, for example. The other point that needs to be discussed is how to load film. It’s a little tricky at first if you are used to loading 35mm film into a typical SLR. With the Minolta, users just have to place the front of the film onto the spool and let the camera take in the film. Hard to explain, but once you get the hang of it, it works beautifully.

So how about the results?

More results of the Minolta 125 can be viewed on the Lomography site here.

The cons

This is probably not the camera for an advanced amateur and certainly not for a professional looking for complete control of the settings.

I am thinking the camera is perfect for the upstart Lomography student looking to have some fun with print film at a reasonable cost. Or a photographer looking for a second camera to use as a simple point-and-shoot.

Unlike so many of today’s digital point-and-shoots, this has a decent viewfinder –maybe a little small – but entirely usable.

It’s a fun camera to grab quick shots. For a street photographer, it gives you quick power up and good autofocus with a nice range of focal lengths that are more than capable of getting the job done.

Its compact form is never going to suggest that you are shooting professionally, but its reach at 125mm will give you lots of opportunity to keep a comfortable working distance.

Before and After

The before and after shows the original colour image and finished B&W after processing with Luminar Neo.

It’s the camera to pop in your pocket for a fun night out or a party where getting results is more important than capturing fine photographic images. The strength and simplicity of the flash makes it ideal to capture party portraits. The night mode makes getting night portraits with city lights in the background a simple process.

That’s not to say the camera is not capable of great results.

If you are more serious, put the camera on a tripod and use the electronic self timer to capture impressive results with Minolta’s high-quality lens.

The B&H price in 2001 for the Freedom Zoom 150 with an extended zoom range of 150mm, 25mm for than the sister camera the Freedom Zoom 125.

Look for a good used camera and put it to use. For the price you’ll likely pay, there is no need to worry about it either being damaged or stolen.

In its day, it was considered a sweet little point and shoot. Certainly not the most inexpensive camera in the year 2000. It sold at many of the large New York camera retailers for more than $200. The advertisement shows the B&H price of the Riva 150 at $224.00.

Today, you can probably pick one up for easily less than $100.

That’s a steal for a good working copy.

Post processing with Lightroom and Luminar Neo

Today’s print film offers the photographer plenty of exposure latitude. The above images were shot with Kodak 200 film and scanned on an Epson 500 flatbed scanner.

The initial edit from a high resolution TIFF scan to a jpeg was done in Lightroom. (I have included some of these digital images above.)

Then, I brought the jpeg images into Luminar Neo and went to work on transforming the images into the more creative visions I imagined when I was taking the photographs.

Luminar Neo’s modules allow for a more creative approach to editing your work, if that is the direction you want to take your images. That’s not to say that other post processing programs (including Lightroom and Photoshop) are not capable of similar results, it’s just the these creative processes are built into Luminar Neo.

The ability to try the creative filters will inspire you to experiment more and come away with a more creative finished result.

Whether you like to add a creative touch to your images, or prefer to leave them as they are straight out of the camera, Luminar Neo offers the photographer the ability to make that choice.

Luminar Neo post processing software

If you want more information on how I use Luminar Neo to post process my photos, take a moment to check out my other posts listed below:

• The beauty of the woodland with Luminar Neo

• Can Luminar Neo stand on its own as a post processing package?

• A Walk in the Woods: A Photographic Approach

If you are interested in purchasing Luminar Neo, please consider using the code FernsFeathers at checkout to receive a 10 per cent discount. By using this code, I receive a small percentage of the proceeds which helps me to continue producing articles for readers.

Focus on the Pentax Q’s 08 rare and wonderful wide angle lens

Wide angle photography is taken to a whole new level with the Pentax Q and 08 extreme wide angle lens.

This sunset image shows the impressive results that are capable with the Pentax Q cameras and the 08 wide angle lens.

Another tiny but tough-to-beat legendary Pentax lens

Pentax has made more than its share of legendary lenses, but nothing really comes close to the rare and relatively unknown (except to Q-series owners) 08 wide angle lens.

Why? Because it’s so small and sharp that it defies logic.

In December of 2013, Pentax released their final Q-series lens for their diminutive, mirrorless Q-series cameras. This 17-33mm equivalent lens (depending on the Q camera used) originally sold for almost $500 US and could pass for a 50mm, M-series lens, accept it’s probably smaller and lighter.

Today you would probably be hard pressed to find one much cheaper than the original price thanks, in part, to a combination of quality and rarity.

This garden image was photographed with the Q7 and the 08 extreme wide angle lens. Note the strong colours together with the edge-to edge sharpness.

Of course the whole Q-series of cameras and lenses are ridiculously tiny. The 08 wide angle lens in the Pentax Q “high performance” lens series follows in those same footsteps, but it’s still mind boggling that a lens packing this kind of punch can be this small, have image quality that matches and surpasses some of the finest 35mm equivalent lenses, and boasts such a high-quality build standard.

Pity that so few photographers will ever get the opportunity to run it through its paces. Thankfully, I’m not one of them.

I was able to purchase the lens as part of an entire Q7 series that included the 01 (nifty 50mm), the 02 wide angle, the 06 (70-200 f2.8), the fisheye and the mount shield lens. Despite already owning most of the lenses, let’s just say the offer was too good to refuse.

One of several waterfalls images that shows the incredible capabilities of the original Pentax Q camera together with the approximate 17-30mm wide angle lens. This image was shot using an accessory waist level finder (see below) and post processed with Luminar Neo. (see below for details on how you can get 10 per cent off of Luminar Neo with my special code.

“It’s still mind boggling that a lens packing this kind of punch can be this small, have image quality that matches and surpasses some of the finest 35mm equivalent lenses, and boasts such a high-quality build standard.”

This Pentax lens packs a punch

But we are here to focus on one lens only – the Pentax 08 wide angle lens.

Chart provided courtesy of Pentax Users Discussion Group.

First, it’s important to remind Q-series camera users that the various cameras in the lineup have different sized sensors that affect the focal length of the lenses. In the case of the 08 wide angle gem, the different sized sensors mean that the 08’s focal range is equivalent to approximately 21 to 33 mm in the full-frame (24 x 36 mm) format when used on an original Q or Q10 camera, and 17.5 to 27 mm when used on a Q7.

Add to the excellent build quality, wide focal length and miniature size, an image quality that again, defies most logic.

For more Pentax Q-series images with the 08 wide angle lens, be sure to check out my photo gallery here.

This image is one of a series taken on a one-day visit to downtown Toronto. The Pentax Q series of cameras together with the 08 are a great combination for architecture or street photography. Add the waist level finder accessory (see below) and no one would suspect you are taking serious street images.

Sharp throughout; including the corners; excellent distortion control; built-in ND filter, and shutter which prevents rolling shutter and synchronizes with the built-in flash; a built-in autofocus motor that features a quick-shift which allows the photographer to manually fine tune focus without switching out of autofocus mode. There is also a plastic tulip-style lens hood available, (sold separately). The lens mount is made of metal and the front element accepts the traditional 49 mm lens filters.

What more could you ask for in an extreme wide angle lens.

Suffice it to say it’s incredibly wide for such a tiny camera sensor, and with that comes all the challenges the world of wide angle photography presents.

You might think that using an extreme wide angle lens is easy, but that would be a mistake. Even though I have owned the lens for close to a year, maximizing its unique characteristics comes with a whole set of challenges.

This garden image makes use of strong foreground grasses and a misty morning to keep the image simple.

Now, if I lived in an area of epic landscapes, maximizing extreme wide angle lenses would be a whole lot easier. Unfortunately, epic landscapes are hard to come by where I live. Successful extreme wide angle photography begs for simplicity and finding natural images that work with a wide-angle lens takes time and a whole lot of patience.

Nevertheless, in time, I’ve collected a decent selection of images exploring the potential of the lens. I’m sure the lens will be put to the test many more times in the near future and I will try to add them both to this post as well as my photo gallery of Pentax 08 images here.

What others are saying about the Pentax 08 wide angle lens

The following are just a few comments from Pentax Q-series owners who have made images with the 08 wide angle lens.

Tiny but Tough

Pentax’s Q-series 08 wide angle lens is both rare and wonderful with exquisite image quality and very high build quality. Image provided by the Pentax Discussion users group.

From the Pentax Forums discussion group:

“In 2019, I still do not know what beats the Q-system with this and the 06 tele-zoom. As for sharpness, this lens is as good as it gets on the sensors in the Q's. Bokeh is impossible: shoot in BC mode if you need that, but, really, just bokeh in post if you need that. This lens is crazy unique, which alone makes it crazy good.”

“After a few test shots, I believe that this is the perfect lens for the Q system. It's as sharp as the 01, yet incredibly small for an ultra wide. It's almost unbelievable how Pentax has made such a marvelous feat of a lens! Now, if only Ricoh did not scrimp on a hood. With a 06 on Q, and 08 on Q7, and 01 on standby, I'm all set.”

“I was a bit hesitating before purchasing this lens due to the steep pricing (nearly cost as much as I spent on 01+02+06 all together). However, once I received my copy and started shooting with it, all my concerns went away. What a lens! It is certainly compact, quite a bit smaller than 02 or 06 lens. The amazing thing is the IQ, corner sharpness smashed my DA* 16-50. In fact, it is one of the sharpest wide angle lens I have ever seen. Colour reproduction is great, which makes RAW file super easy to work with. To sum up, for any one who owns a Q system camera, this lens is a must_have!”

Waist level finder

This waist level finder accessory from Temu allows the photographer to get the camera at a lower angle or use it more like a view camera. It has no electronics to hook into the camera but is handy to get a different perspective.

Add a waist level viewfinder to your Pentax Q

For most of the waterfall images shot with the Pentax Q and 08 lens, I used an ingenious accessory that allowed me to to get very low and better use foreground elements in the image.

The accessory brings back memories of my beloved Pentax LX with waist level viewfinder, except it can be used on any camera with a hot or cold shoe including the Pentax Q series of cameras. No information is transferred from the camera to the finder, so it is only for compositional purposes. I purchased it primarily for my coveted Sigma DP2 with its 42mm fixed focal length, but it allows me to get a good feeling for what’s in the frame of any camera, especially one that lacks a flip-up digital screen.

I purchased this waist level finder from Temu for less than $60 Cdn. That amounts to about $44 American. I also purchased some very nicely made camera straps at the same time.

Similar waist level finders are also available on Amazon.

For more on both the waist level finder and camera straps, click on the above links.

Finder is ideal fit for Q-series

The accessory waist level finder is handy for all sorts of photographic situations, especially if you want to get low and see the image in a top-down view..

The well-built, waist level finder has markings for a 40mm lens but goes out to about 28mm. It’s a far cry from the 17mm available on the Q-series 08 lens, but it gave me a good idea of the image I would obtain when the camera was set so low that I could not use the back LCD screen with any success.

It is ideal for the 02 lens and the 01 lenses, but will get called on for a number of my digital point-and-shoot cameras when I need to get low or just want to have some fun with the waist-level finder.

The extreme wide angle lens allowed me to take advantage of strong foreground objects including the small waterfalls and rocks.

Conclusion: It’s not always about size

Imagine heading out for a day of photography with a Pentax Q, the 08 wide angle, the 01 nifty fifty and the 06 telephoto slipped into your jacket pocket. Heck you might as well add the 02, a couple of toy lenses and the mount shield lens to round out your gear since everything fits nicely into two pockets or a small camera bag.

Just having a capable camera with you whenever you go out can do wonders for your photographic development. I love my cell phone, but give me a camera with a couple of sweet lenses any day over a phone. And that’s where the Pentax Q line of cameras and lenses really can’t be beat.

These things might be tiny but they aren’t toys. In fact, without the anti-aliasing screen that Pentax chose to eliminate on these cameras, you can shoot them in RAW DNG format with sweet Pentax lenses and get excellent results.

I’m hoping some of the images in this post and on my 08 photo gallery will inspire Q shooters and disbelievers to rethink what is possible with these exceptional mirrorless camera systems.

If you are interested in purchasing Luminar Neo, please consider using the code FernsFeathers at checkout to receive a 10 per cent discount. By using this code, I receive a small percentage of the proceeds which helps me to continue producing articles for readers.

Sigma DP2: Capturing unrivaled detail with a compact camera

Sigma’s DP2 enthusiast camera has a cult following of photographers looking for the highest quality images in a simple point-and-shoot camera.

It’s a love-hate relationship based on the Foveon sensor

If you know anything about Sigma Foveon cameras, you’ll understand the love-hate relationship owners develop with these coveted little point-and-shoots.

We love them for the quality of the pictures that are possible with such a simple point-and-shoot camera. At the same time, however, we hate them for just about everything else.

For me, love of the final results wins out every time.

It’s almost always about image quality.

Sigma DP2 is a high-end point and shoot camera complete with an APS-C sized foveon sensor.

I have to admit, however, I’m growing to love the quirky little “features” of this camera – from its noisy start-up to its minimalist design. That simple design is hard to ignore, and you can’t help but compare it to the simplicity of the iconic Leica cameras. Even the back buttons’ black-on-black design (making it impossible to read the button functions) is divine. (Although I have read many reviews from photographers unable to appreciate the minimalist approach.)

All you have to do is watch this interview with Sigma CEO Kazuto Yamaki to get a better understanding of Sigma’s approach and direction to minimalist design.

Please take a moment to check out my Gallery of Images taken with the Sigma DP2 here.

Sigma Foveon pros and cons

For those who may not be familiar with these very specialized cameras, let’s explore for a moment what makes them special.

It’s the sensor!

Just like the older, CCD-sensor-based cameras are highly sought after, the Foveon-based Sigma sensor cameras are coveted by those photographers looking for the best possible images out of a pocketable, point-and-shoot camera.

And the Foveon sensor built into these cameras truly delivers.

‘Why, what’s the big deal,?’ you may ask.

Without getting into all the complexities of how a sensor is made, suffice it to say that the Sigma’s very unique Foveon sensor is actually three sensors sandwiched together to extract the red, blue and green (RBG) colours that combine to give us the full spectrum of colours.

Other cameras use a single sensor to extract the red, green and blue spectrums of light. Sigma uses three sensors in its Foveon-based cameras.

The result is a very complex system that maximizes not only the colour, but the fine detail and micro contrast in the images. Most photographers will agree that the Foveon sensor is the reason the images have the most film-like look right out of the camera.

You may or may not agree, but it’s difficult to argue that these images don’t have a special quality to them that is hard to ignore and even harder to replicate with other, non-foveon sensors.

A simple comparison between the DP1 and DP2 shows similarities in all but the lens size, battery life and ISO capabilities.

Why do so many photographers dislike Sigma cameras?

What are the cons of this love-hate relationship?

I have the Sigma DP2, so this review is based on that camera.

This love/hate relationship starts when you turn it on. The camera makes some weird squeaky grinding noise that can be quite concerning when you first hear it turn on and the lens pops out. The first time I turned it on, I was sure it was broken. However, that’s just the sound of a DP2 turning on. I can certainly live with that. In fact, the more I hear it, the more I’m even beginning to like that sound.

If that was the only negative, we would have little to complain about. But, of course, it’s only the beginning.

Heavily cropped image

This heavily cropped image shows the capabilities on the RAW images. Despite the extremely heavy crop, the image holds together showing incredible detail and colours.