The Mayapple: Carolinian zone woodland native wildflower

Early spring is the time for Mayapples to spread out across the forest floor and our woodland gardens. The spring ephemerals are native to southern Ontario and northeastern United States but stretch as far north as Quebec and as far south as Florida.

Tips for growing Mayapple in the woodland garden

Inspiration in the garden comes from many sources.

Gardens around our neighbourhood are often a good starting point. So too are our favourite gardeners on social media like Instagram and Youtube. The gardeners I follow are a constant source of new ideas and inspiration.

But for woodland gardeners the best source of inspiration is undoubtedly a local woodlot full of native plants trees and shrubs. (For article on the importance of native plants in the garden go here.

My woodland Mayapple inspiration can be traced back 20, maybe 30 years when, as a nature photographer, I roamed the woods in southern Ontario photographing wildflowers and anything else I could focus on.

That’s where I first encountered the Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum).

This lovely swath of Mayapple grows wild near our home. When I stumbled upon it in the early spring it inspired me to consider growing large swaths of the ephemeral, underutilized native wildflower in our woodland garden.

Mayapple is one of the first Carolinian zone wildlflowers to emerge in the spring in the woodlands of southern Ontario and the northeastern United States, so it became a magnet for many of us photographers just looking for something, anything, to focus on in the early spring woodlands.

So, you can imagine that it didn’t take long for me to start growing a clump in my yard. Turns out it was so successful that I was able to spread it around where it continues to thrive in swaths throughout the garden.

The Mayapple is actually in the Barberry family and grows naturally everywhere in the eastern half of the United States stretching as far north as Quebec and south to Florida and Texas.

You’ll find Mayapple most often growing in moist, open woods and often growing on the edges of boggy meadows in zones 3 to 8. Although it enjoys moist woodlands, it does well in dry woodlands where, once colonized, can tolerate some drought.

These handsome plants are not just lookers, they are a larval host plant for the golden borer moth and the Mayapple borer.

Large colonies of Mayapple can be found growing from a single underground rhizoid stem where the central stalk of the plant emerges wrapped in either a single tightly furled leaf or a pair or more of leaves that slowly unfurl revealing mature specimens stretching 14 to 18 inches (30-40 cm) in height and blanketing large patches of ground completely shading the forest floor. The single leaf stems do not produce a flower or fruit, while the stems with two or more leaves produce 1-8 flowers in the axil between the leaves. The umbrella-like leaves can spread out 20-40 cm in diameter with 3-9 shallow to deeply cut lobes.

Any other plant with deeply-cut leaves like the Mayapple would be a superstar in most gardens but our native Mayapple suffers from a lack of notoriety in most traditional gardens.

Its beauty is certainly subtle.

Unlike the trillium that shines on the forest floor and lets all of us know when it’s in bloom, the Mayapple goes to great lengths to disguise its flower and the resulting fruit (a small golden apple-like fruit), even creating an umbrella to hide its large white flower from peering eyes.

Much like a hosta in a traditional garden, the Mayapple is mostly a quiet groundcover in the woodland garden. In fact, if you don’t get down on your hands and knees and peek under the large umbrella-like leaf, you may never even know that the plant is sporting a flower in the early spring and yellow fruit in the summer through fall.

Where to plant Mayapple in our garden

But that’s okay. We all need a little quiet in the garden and that’s where the Mayapple really shines.

As I write this in late April, my woodland garden is quite bare. But the Mayapple have already poked their heads out of the soil and are unfurling their large leaves to create a lush sea of green that continues to spreads each year throughout our woodland.

Anywhere in the garden where you have open shade or dappled sun and are looking for a natural groundcover is a good spot to consider planting Mayapple. Although it is considered a spring ephemeral and will go dormant in the summer, its spent leaves, stem and fruit are on display for a good part of the year.

Like many spring ephemerals, Mayapples like moist, humusy well-drained, slightly acidy to neutral soil.

The fruit ripens by late June into July and provides a food source for the fauna in our garden.

“Growing a natural habitat garden is also one of the most important things each of us can do to help restore a little order to a disordered world.”

Also known as Mandrake or the ground lemon, it’s important to note that the Mayapple is a toxic plant. The fruit, even the seeds of the fruit can be toxic. As the fruit ripens it becomes less toxic but unless you do your homework on this plant, it is best to grow it for the fauna in the garden rather than consider it edible in any way.

Chances are the neighbourhood raccoons and squirrels will get to the pungent odor of the ripened fruit long before you do anyway. The fruit ripens by late August and is a real treat for the deer and chipmunks in our garden who know precisely when it is safe to eat.

If you have not yet tried Mayapple in your woodland garden, consider growing a few plants in a quiet, shady corner of your garden. It won’t take long before you appreciate this seldom used plant for its early spring carpet of green, and interesting large leaves that will ring in your spring woodland garden.

Don’t be surprised if it makes itself at home and forms a lovely spring carpet of green right at the time you are craving a little green growth in the garden.

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

Serviceberry the perfect native tree for the garden

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

Native plants source in Ontario

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

Bringing Nature Home by Douglas Tellamy

A little Love for the Black-Eyed Susan

As an affiliate marketer with Amazon or other marketing companies, I earn money from qualifying purchases.

Native Plants find a home on Vancouver Island

Satinflower Nurseries Native Plants owners Kristen and James Miskelly are reshaping and rewilding the gardens and natural areas around Canada’s beautiful city of Victoria on Vancouver Island. The couple is bringing their expertise of native plants to gardeners, and large commericial clients and restoring the natural habitat of the Saanich area.

Satinflower Nurseries Native Plants working to rewild Canada’s gardening paradise

Kristen Miskelly has travelled a long way to find her new home near Victoria B.C.

In fact, it would be harder to find a location in Canada much farther from her Toronto-area roots than her current home on the Saanich Peninsula northeast of Victoria, British Columbia.

But there’s no doubt in her mind that Vancouver Island – undoubtedly one of the finest area in Canada to garden – is her new home.

It’s also the home of Satinflower Nurseries Native Plants, seeds & Consulting (formerly Saanich Native Plants), the business Kristen and her husband, James, have grown from a seed of an idea into a highly successful native plant nursery and consulting firm.

Satinflower Nurseries Native Plants, seeds & Consulting offers a robust retail side to their business, but much of the nursery’s work involves consulting and installation of much larger properties in and around the Victoria area ranging from private lands restoration to commercial and government. The native plant nursery is helping to rewild the land around Victoria B.C.

(For more information on West Coast native plants and garden design, be sure to check out my comprehensive post on Seattle landscape designer Alexa LeBouef Brooks. Also, Check out Alexa’s Pacific Northwest front garden design plan complete with plant list.)

Also, if you are interested in native plants, be sure to check out my post on Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest.

Satinflower Nurseries Native Plants (formerly Saanich Native Plants) is an excellent source of native wildflowers, shrubs and trees for westerly residents especially in the Victoria-area.

For my article on the the importance of using native plants in our garden, go here.

“I absolutely love the Victoria area,” she says. “It’s an absolutely beautiful place.”

It’s not surprising that Kristen, who was born in Welland Ontario but from grade 4 to 12 lived in Aurora just north of Toronto, is in love with the stunningly beautiful landscapes and moderate weather that makes Vancouver Island such a special place. The Saanich Peninsula, once a farming region, is surrounded by water on all sides and continues to feature pastures and an abundance of rolling hills. It’s hard to imagine a more perfect place for a couple with a great love for gardening and native plants.

“We’ve built our business on the core principle of valuing nature. We try to continually work with integrity and excellence and value collaboration greatly.”

It’s the ideal canvas to begin the work of rewilding with native plants, with the goal of helping to bring back much of the rich variety of plants, trees, insects and animals to the area.

Their work has not gone unnoticed. In fact, Satinflower Nurseries Native Plants, seeds & Consulting (Saanich Native Plants) was the recipient of the area’s 2016 environmental award in business achievement.

“I love growing indigenous plants and there is no part of the year we can’t work on them here at our nursery,” she explains on a cold, snowy, mid-February day in Ontario. “We are just planting up some grasses here today.” she adds.

Kristen knew she was home when she left Ontario to begin her studies at the University of Victoria, where she completed both her undergraduate work and a Master of Science in Biology. Her undergraduate work focused on grass taxonomy and her Masters research used palynology – the study of pollen grains – to learn more about the ancient vegetation of southern Vancouver Island.

Her husband, James, has similar expertise. The co-founder of Satinflower Nurseries Native Plants is a biologist with expertise in Garry Oak ecosystems, plants, insects, and restoration. He has a Master of Science in Biology, also from the University of Victoria.

So, it’s no surprise that upon graduation the couple went to work establishing the roots of what soon would become their prosperous native plant business.

“James and I made a decision that when I finished my Masters degree we would begin working more intensively with native plants.” Afterall, she admits, they “were both obsessed with native plants.”

• If you are considering creating a meadow in your front or backyard, be sure to check out The Making of a Meadow post for a landscape designer’s take on making a meadow in her own front yard.

Meadow plants put on a show at one of the Nursery’s locations.

Their nursery took root in 2013 at Haliburton Community Organic Farm, where they had been working as volunteers to coordinate the restoration of a native meadow and wetland. They used a small front lawn of the farm house as their retail outlet for what would become the Saanich Native Plants Nursery & Consulting business (now known as Satinflower Nurseries Native Plants and seeds.) In 2015, they leased an additional half acre at Haliburton Farm for plant propagation and native seed production and in 2018 expanded their native seed fields further to Fairfield Farm just outside of the Victoria core. Kristen emphasizes how grateful both her and James are for the opportunities that the non-profit Society who runs the farm has provided to them and the broader community.

Growing popularity of native plants

From those simple roots rose a successful small business that now employs up to 10 employees over the course of the year and features more than 200 native plants, a large, ever-growing native seed catalogue, several planting fields and soon, a new home for the growing business.

The couple have recently purchased a property in Metchosin near Victoria and plan to use it as a base for their growing business. The new 2-acre property will be staged as growing fields for both plants and seed production. The nursery grows most of its own plants from seed and offers a large selection of seeds at both the commercial and retail level.

Although Satinflower Nurseries Native Plants offers a robust retail side to their business, much of the work involves consulting and installation of much larger properties in and around the Victoria area ranging from private lands restoration to commercial and government.

The new, larger location may be illustrative of the growing popularity of native plants not just on Vancouver Island but across Canada, the United States and Europe.

Kristen says it’s difficult to tell if the expansion of Satinflower Nurseries Native Plants and Seeds is a natural progression of the business or the result of a surge in the interest of using native plants in the gardens of both homeowners and in large scale commercial settings and government projects. But, she is quick to add that with the emergence of social media groups such as Facebook, native plant groups and on-line discussion groups represent “a change in education outreach in society.”

“There is a genuine interest in restoration and conserving nature,” Kristen explains. People are seeing “more habitat destruction every day and they are trying to find something proactive to do to counter that devastation.”

“Sometimes,” she adds, “just planting a few native wildflowers in your garden exposes you to the joys and benefits of using native plants and from there, the enthusiasm just grows.”

Satinflower Nurseries Native Plants and Seeds is certainly playing a role in conserving nature and helping to educate gardeners in their area about the importance of using native plants.

Besides teaching a range of courses and workshops related to plant identification, botany, restoration, and propagation, Kristen currently teaches Ecosystem Design through Propagation of Native Plants and Urban Restoration and Sustainable Agricultural Systems at the University of Victoria.

Their website states that the company’s aim is to inspire and empower people to restore and conserve nature by providing native plants, seeds, education, and expertise.

Education and outreach make up the foundation of the nursery. Here Beangka Elliot, Tsartlip First Nation, co-hosts one of the nursery’s regular educational workshops.

Expertise at the root of Nursery’s success

When it comes to expertise, it would be difficult to find a more knowledgeable staff than the folks at Saanich Native Plants. You already know about Kristen’s expertise, her husband, James, has his own expertise in Garry Oak ecosystems. His Master of Science focused on butterflies and their habitat needs. Besides his work in various capacities in rare plants and animals, he is a research associate at the Royal BC Museum in entomology with a focus on Canadian Orthoptera (crickets, grasshoppers and katydids.) For his day job, James works with Natural Resources Canada, where he helps to conserve and restore habitats and rare species of Federal Department of National Defence (DND) lands.

At the nursery, James plays a role in the consulting aspects of the nursery that often works on larger government projects. In addition, he manages the native seed fields and develops specialized seed mixes for nursery customers.

But that really is just the beginning of the expertise the nursery offers customers. Julia Daly, with a BSc in Geography from the University of Victoria and a diploma in Applied Coastal Ecology from Northwest Community College, puts her knowledge of plant identification, species-at-risk management, ecological restoration, and native plant gardening to work at the nursery.

Andrea Simmonds brings new perspectives to native plant garden installations with her artistic background and her patient and kind demeanor is always welcome when working with a range of clientele.

Josh Aitken brings extensive experience from working on farms growing up in rural Australia and Paige Erickson-McGee brings a passion for conservation and knowledge of native plants along with her BSc Geography from UVic and an Environmental Technologist diploma from a local College.

Sasha Kubicek brings an extensive knowledge of local orchids and protecting orchid habitats. He and his wife, Robin, oversee the seed saving part of Sea Bluff Farm – a 10 acre certified organic vegetable farm with a 600-foot section set aside as a native pollinator hedge row. They are also actively rehabilitating the farm’s Garry Oak grove.

Daniela Toriola-Lafuente moved to Victoria in 2012 from France after obtaining her BSc in natural sciences at the University of Lausanne and PhD in tropical forest ecology at the University of Paris. One of her passions is propagating native plants and taking great pleasure that her work is having a positive ecological impact.

Other consultants and partners bring a diversity of expertise and perspectives. Beangka Elliott from the Tsartlip First Nation of WSÁNEĆ (Saanich) Territory has a background in sharing traditional knowledges of Indigenous foods and medicines through workshop-based learning. Beangka started working at Saanich Native Plants in 2018 in propagation as well as providing workshops on a variety of topics. Beangka, no longer a regular employee, leads a suite of regular workshops at the nursery with a focus on consent-based practices and Indigenous foods and food systems.

Kristen points out that although many of the people who make up the nursery team have impressive credentials, nothing replaces a “passion for native plants. When we hire we are looking for that authentic passion – everything else can be learned.”

“Expertise is important when you are selling indigenous plants,” explains Kristen. Many of the plants are not well known to the general population so Kristen and her staff consider it vital to be able to pass on their knowledge on the care of the plants and educating clients to know what they are planting and how the plants will perform in various growing conditions.

She also emphasizes that land stewardship by Indigenous Peoples, past and present, continues to play a critical role in the awareness of the importance of native plants and natural areas in the Victoria area.

We’ve built our business on the core principle of valuing nature. We try to continually work with integrity and excellence and value collaboration greatly,” states the introduction on their website.

The nursery grows plants and produce seeds native to a variety of habitats in the Victoria area, including meadows, woodlands, forests, wetlands and beaches. The company also specializes in the restoration and ecology of Garry Oak ecosystems (Prairie-Oak ecosystems in Ontario and the southeast United States) and meadowscaping.

The native plant seed rows at Satinflower Nurseries Native Plants, seeds & Consulting provide a stunning visual display as well as habitat for wildlife.

Their commitment to the environment is evident in the fact that no herbicides or pesticides (including neonicotinoids) or chemical fertilizers are used in their business.

Although it would be easy to think that everything grows perfectly on Vancouver Island, that would be a false presumption. Kristen explains that annual precipitation across the Island varies greatly, ranging from rainforest on the westcoast to Mediterranean-like to the southeast

In Saanich, where the Nursery is located, it is in the “rainshadow of the Olympic Mountains resulting in extremely droughty summers,” explains Kristen. In fact, the location has the lowest average summer precipitation anywhere in Canada. “Even Vancouver gets two times the rainfall we do,” she explains. “Just a couple hours from where we are is rainforest.”

All this means that the native plants they grow are very focused to a specific geographical area. Kristen explains that their growing zone is part of a broader ecoregion that extends into Washington and Oregon.

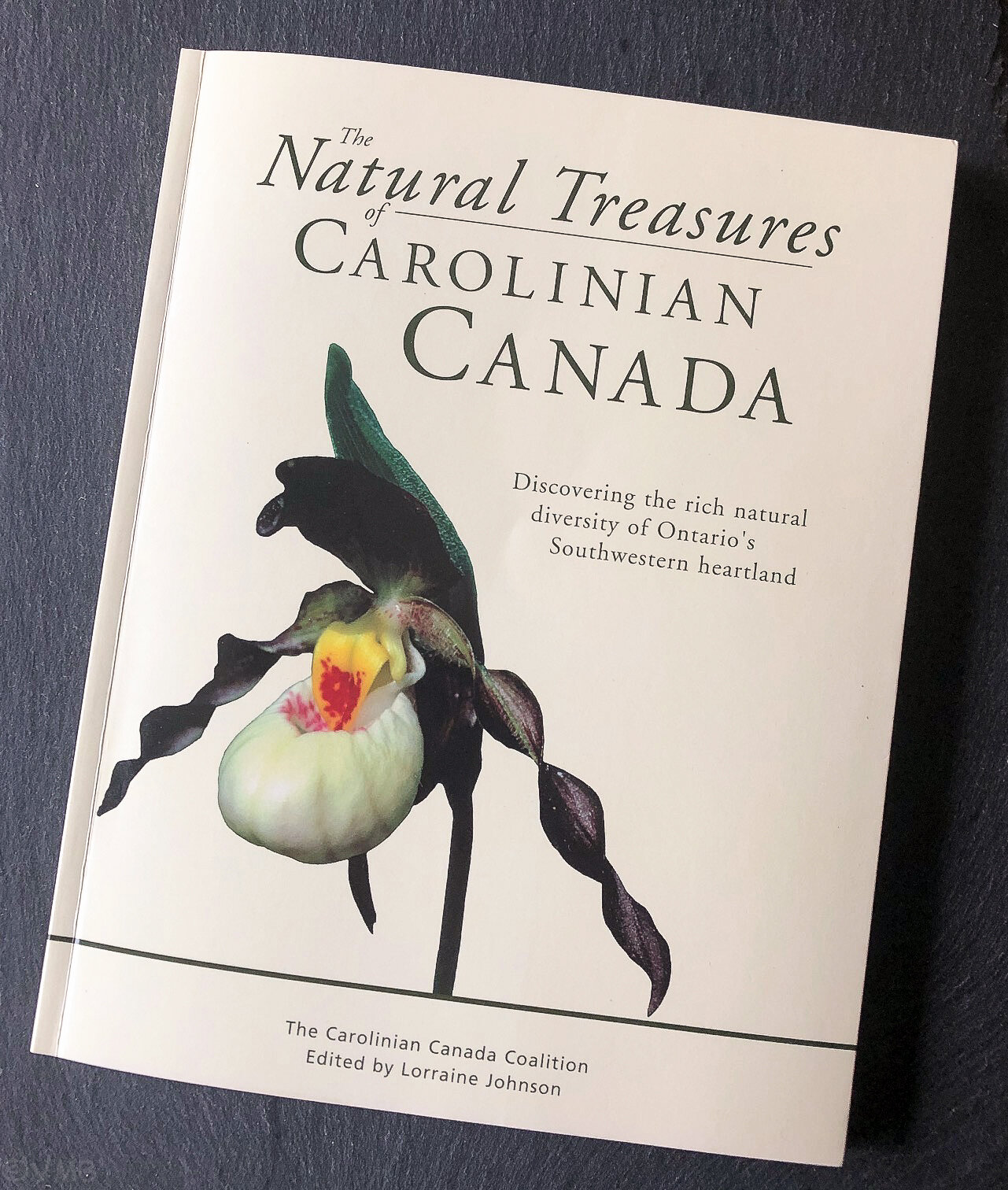

Kristen and James love returning to Kristen’s roots in Ontario to experience the diverse range of flora and fauna of the Carolinian zone in Southern Ontario. She points out that her former home in Ontario is very biodiverse, having a wider variety of both flora and fauna than they enjoy on the Saanich Peninsula.

Bringing in the butterflies

Sometimes a single plant in a homeowners garden can inspire them to explore more native plants, explains Kristen. Every time we see wildlife using the native plants, it serves as endless inspiration to keep doing the work that we are doing.

The social activism and access to nature that many BC residents enjoy has resulted in an engagement with nature that she also hopes is being felt in Ontario as well. Kristen notes that “The gardeners, conservationists, and environmentalists in Ontario who have been working to educate others on the importance of native plants serve as inspiration for others”.

On an earlier visit to Ontario, the couple were particlarly impressed with the massive growing facilities at St. Williams Nursery & Ecology Centre in Norfolk County in the heart of southwestern Ontario’s Carolinian Life Zone. The largest native plant nursery in Ontario, stretches some 6 acres of greenhouses and more that 250 acres of production fields, is a wholesale conservation nursery and ecological restoration provider. Its team of restoration scientists and practitioners, nursery growers, and technical experts support and supply a variety of conservation initiatives across the province of Ontario.

Kristen and James have also spent time with Ontario Naturalists Mary Gartshore and Peter Carson who started Pterophylla in old South Walsingham. Peter and Mary worked to restore a 60-acre Tobacco farm back to black oak savanna and forest. Kristen notes that the “Pterophylla restoration project continues to be a tremendous example of what conservation impacts hands-on restoration by individuals can have”.

It’s always exciting to see how others operate their nurseries and get new ideas, she says. Places like St. Williams have greatly inspired us.

What’s the future hold for Satinflower Nurseries Native Plants, seeds & Consulting? The couple are busy preparing their new nursery location in Metchosin with everything from installing irrigation to re-planting their native seed fields. The Nursery is also re-doing their website in an effort to provide more online educational resources for the public. The new website will also feature a digital newsletter and online store to make native plants and seeds more easily available to everyone in their area. If you haven’t already, be sure to check out the impressive new Ontario Native Plants’ website.

Readers in Canada’s west who are looking for homegrown native plants need to check out Saanich Native Plants.

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

Serviceberry the perfect native tree for the garden

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

Native plants source in Ontario

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

Bringing Nature Home by Douglas Tellamy

A little Love for the Black-Eyed Susan

Native moss in our gardens

As an affiliate marketer with Amazon or other marketing companies, I earn money from qualifying purchases.

Ontario Native Plants: Taking back nature one garden at a time

Reyna Matties and Ontario Native Plants is saving our natural environment one garden at a time. The Hamilton-based native plant on-line store offers more than 100 plants, shrubs and trees native to Ontario and the Carolinian Canada forest zone to shoppers on their informative on-line catalogue.

McMaster grad brings native plants to Ontario

Reyna Matties knows her native plants, and she knows how important they are in urban revitalization, restoration and sustainability.

The 30-year-old manager of Ontario Native Plants (onplants.ca) is using that wealth of knowledge in her mission to bring back native plants to Ontario one garden at a time.

For my article on why native plants are important in the garden, go here.

What is Ontario Native Plants?

Ontario Native Plants (onplants.ca) is a Southern-Ontario mail order company, based out of Hamilton, that specializes in providing an impressive selection of native plants, shrubs and trees to Ontario residents. They offer more than 100 varieties of native plants. To ensure clients get only the hardiest plants native to their agricultural zone, Ontario Native Plants only delivers to Ontario residents.

It all started for Matties at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario where she earned a bachelors of Science (Environmental Science) and a Masters of Science (Biology). But it wasn’t until she embarked on her Masters thesis project that her love of native plants took root.

Her thesis focused on analyzing the success of a new parking lot restoration project on the McMaster campus. Part of the restoration involved the extension of a riparian buffer to protect a creek habitat from water runoff of a large campus parking lot.

“Being able to provide habitat and a food source for the local wildlife that visit your yard is such a beautiful and important motivation.”

The creation of the buffer called for the extensive seeding with a mixture of hardy prairie native plants (rye, bergamot, rudbeckia, etc.). Plant and soil studies were done to assess the success of the restoration (i.e. proportion of native to non-native plants).

Reyna Matties with a selection of native wildflowers from the ONP greenhouses.

The research created an impressive native-plant knowledge base and she landed the manager’s position for the small upstart company in 2019. Ontario Native Plants actually started in 2017, the same year Reyna graduated from McMaster. The job seemed too perfect to be true, combining her education with a desire to make a significant environmental impact.

The McMaster project, Reyna explains, “grew an interest of mine in urban planting and green infrastructure in cities. More specifically, I became interested in how people perceive restoration work and planting native in general.”

“I wanted to work at a plant nursery or business that helped with ecological restoration, or connecting home owners to native plants. The ONP manager job ticked all my boxes of what type of work I wanted to be involved in, and also provided a diversity of roles to learn from in a new small business.”

A bouquet of wildflowers from ONP.

Needless to say, the business literally took off after Reyna came on board in the spring of 2019. Today, the on-line mail order business is enjoying great success with a strong on-line social media presence and word-of-mouth advertising.

In 2019, ONP had a crew of about four people during the busy period between May and June. For 2020 that number almost doubled to about seven people and Reyna says that number is expected to grow again in 2021.

“The last two years (2019 and 2020) have been very important for our growth as a business,” Reyna explains.

She has great praise for the staff that have played a key role in ensuring the success of the business.

“The crews have all been such amazing individuals that enjoy working with plants, and bring so much energy to each day,” she explains.

Part of that success is the result of a growing awareness of the environment and the loss of habitat being experienced worldwide. “The interest for planting native is growing,” she explains. “Being able to provide habitat and a food source for the local wildlife that visit your yard is such a beautiful and important motivation.”

The Covid pandemic is also creating more awareness of gardening and the environmental affects of planting native flowers, trees and shrubs.

Reyna looks over some of the many wildflowers in one of the ONP greenhouses.

“With people staying home more in 2020, there was another natural surge in gardening with homeowners having more time and interest in gardening,” Reyna explains. “The physical and mental benefits are mentioned frequently by our customers.”

“With our store being completely online and contactless, we have been able to provide a very efficient way for people to purchase plants for their gardens. We are excited for 2021 and are busy updating our website and getting organized for our opening on March 1, 2021.”

But taking an upstart, online native plants nursery to new heights takes more than good timing and a growing interest in using native plants in the typical backyard garden. It takes both a knowledge of plants and first-rate service.

Ontario Native Plants seems to have found the perfect combination.

I can attest to this after a work colleague and I placed an order with the company last year. Not only were the plants shipped in a timely and obviously caring manner, the product was vigorous and extremely healthy. It transplanted well and produced in its first year. The cardinal flowers I planted proved to be a simply outstanding addition to our garden and helped to draw in a number of hummingbirds and hummingbird moths that worked the flowers from early to late summer providing me with endless chances to capture excellent photographic images in a natural setting.

“Since we are only an online store, we have been able to focus on creating a very streamlined ordering process. Customers can simply create an account, and then add different plants to their cart. The check-out is also very simple, and payment is processed by credit card or Paypal. (Website: onplants.ca)

By delivering only to Ontario, clients can by assured they will receive only the hardiest plants native to their agricultural zone.

“We only ship within Ontario as our business model is to keep the plants in their native range. We also only grow our plants from Ontario sourced seed, so you can be assured that the plants will be well adapted, and also genetically unique. We provide information on each plant’s hardiness zone for you to determine whether it can grow succesfully in the zone you live.”

Success certainly breeds more success, much to the benefit of their clients.

“We have also been able to add a handful of new species each year and, in 2021, we are offering more than 100 species of flowers, grasses, trees, shrubs, and ferns. Pretty exciting stuff!”

An important part of the ongoing success of the business is a growing awareness of the importance of using native plants in typical urban and suburban gardens rather than more showy hybridized versions of the same plants.

“We work to provide as much information in the plant descriptions about the benefits of each plant to the local wildlife, often an important nectar or food source for a variety of butterflies, caterpillars, moths, etc. We also share articles or information on Facebook and Instagram that highlights the importance of native plants,” Reyna explains.

Three reasons to use native plants

What does Reyna consider the three main reasons for using native plants in our gardens?

1. Food source/habitat for local wildlife. From the nectar from a Blue Lobelia flower, to the acorn of an Oak tree, native plants provide a diverse buffet for local wildlife in your garden. Especially in urban areas where green space is limited, bringing native plants into your yard provides “food along the road” for migrating insects, birds, and other small mammals.

2. Ecological connectivity – pockets of native plants in homeowner gardens help weave back together ecosystems that have been removed. This once again could benefit wildlife with corridors for movement or food, habitat, etc. Native plants also contributes to climate resiliency by cooling urban areas with connected patches of trees, shrubs, flowers, etc.

3. Mental and Physical benefits for the gardener – Digging in the soil and taking time to observe the beauty around you. Noticing the small insects that feed on your plants. Moving compost all day and the satisfaction of the physical labour. There are so many ways to enjoy your garden, and then, in turn, benefit from that enjoyment.

This season ONP is adding 19 new plants to its on-line catalogue of more than 100 plants, shrubs and trees. The on-line catalogue lists 59 perennial species, 48 tree and shrub species (For this year’s new plants, look for the ones listed in bold).

A quick look at the website shows perennial flowers ranging from Wild Columbine (see my earlier article here), Wild Ginger, three types of Milkweed, two types of Joe Pye, Asters, Wild Strawberry, Bottle Gentian, Woodland Sunflower, Rose Mallow, False Solomon’s seal, two types of Beebalm, Yellow Coneflower and Black-eyed Susan.

Grasses listed include Big and Little Bluestem, Switchgrass, Bottlebrush Grass and Indian Grass. Carexes include Bebb’s sedge and Fox sedge. Four ferns are listed including Lady Fern, Marginal Wood Fern and Sensitive Fern.

ONP has an impressive list of 23 trees listed for sale, including Alternative Leaved dogwood, Tulip tree, Eastern Red Cedar, Paper Birch, Paw Paw (see my article here), Eastern redbud (see my article here), Eastern Hemlock, Tamarack, White Cedar and Bur Oak.

There are 25 Shrubs listed including Serviceberry, Black Chokeberry, Flowering Dogwood, two types of Sumac, Elderberry, Lowbush Blueberry and Nannyberry.

Besides individual plants, shrubs, trees and grasses, the catalogue also offers gardeners “plants packs,” perfect for gardeners planning to plant a larger area with more specialized needs. For fern lovers, there are a number of packs offering assorted ferns, or packs of four specific fern types such as lady fern, sensitive fern or wood fern.

In addition, there is a plant pack focused on rain gardens.

The catalogue is organized to provide plenty of assistance to seasoned gardeners as well as novice native gardeners. Not only are the plants broken down according to light requirements (partial shade to shade, full sun, sun to partial shade…) it is also broken down according to moisture requirements and soil type.

Reyna works in one of the greenhouses at ONP headquarters in Southern Ontario.

New gardeners or gardeners new to ordering through ONP should be aware that many of the plants sell out over the course of the spring and summer, so they may want to get their orders in early.

Last season Lowbush blueberry, Elderberry, Pawpaw Tree, Butterfly milkweed and Wild lupine sold out.

In addition to native plants ONP also sells trees and shrubs. In Spring they offer 1-year-old plants, and then by late summer start selling a 4-month-old crop from that year. So trees and shrubs don't sell out as quickly throughout the year.

“With perennials (Flowers, grasses, ferns) there is only one crop seeded either in the prior fall or Spring, so we are able to order more as quantities permit, but those are more in demand. This is why we emphasize ordering as soon as you can to ensure you get the variety you were hoping for in Spring.”

How to place an order

ONP start taking orders on March 1st. Then, begin to ship orders with ONLY trees and shrubs in mid April. All other orders begin to ship in early May. It is essentially a queue so the earlier you order, the earlier your plants will likely be shipped in May.

Ontario Native Plants offers an updates page (https://onplants.ca/updates/) where they post information on what order numbers are shipping and good tips on making up your order.

Western Canada readers should check out Saanich Native Plants

Ferns & Feathers readers in Western Canada, specifically British Columbia, should check out Saanich Native Plants. They grow plants and produce seeds native to a variety of habitats in the Victoria area, including meadows, woodlands, forests, wetlands, beaches and more.

Their impressive website states they aim to inspire and empower people to restore and conserve nature by providing native plants, seeds, education and expertise.

“We’ve built our business on the core principle of valuing nature. We try to continually work with integrity and excellence and value collaboration greatly.”

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

Serviceberry the perfect native tree for the garden

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

Bringing Nature Home by Douglas Tellamy

A little Love for the Black-Eyed Susan

Native moss in our gardens

As an affiliate marketer with Amazon or other marketing companies, I earn money from qualifying purchases.

Native Eastern columbine: Growing tips for a woodland, wildlife garden

The Native Eastern Columbine is an early blooming red and yellow wildflower that is an important food source for returning hummingbirds and other pollinators. Grow them in your woodland wildlife gardens in average to poor soils in rock gardens, woodland edges or garden borders.

First columbine encounter on Niagara Escarpment

I’ll never forget my first sighting of wild native columbine.

I was hiking along the Niagara Escarpment with my camera and stumbled upon two beautiful clumps of the native plant, columbine, in their prime and growing on the edge of an overhanging, steep cliff.

I had to get a shot of them. So, being young and not too bright, I moved way too close to the cliff’s edge to get the images.

Needless to say I got the shots and survived to tell you about it.

Not the best shots maybe, but ones I’ll never forget.

These wildflowers made such an impression on me that day that native columbines were the first wildflowers I planted in our front woodland wildlife garden more than ten years later.

(For my article on why native plants are vital in our gardens, go here.)

Although the Eastern Columbine may look delicate, the plants are actually quite hardy, living for many years, often in quite harsh environments. When I say my first sight of them was growing on a cliff, I wasn’t kidding. These delicate-looking flowers appeared to be growing right out of a crack in the granite cliffs.

Not only did I plant them in my front garden, I also recreated in my garden – at least as best I could – that same image of the columbines growing on the limestone edge of the escarpment.

Our native columbines grow out of, and next to, a large limestone boulder surrounded by clumps of maidenhair ferns. I originally tucked the plant right up beside the edge of the boulder so that it could draw heat from the rock in early spring. It wasn’t long, however, before a plant emerged from a thin pocket of soil along a crack in the rock. These little guys will find a spot to grow anywhere they can. This plant stays more compact than the one growing in the soil beside the rock, but together they create much the same feeling I experienced so many years ago overhanging the cliff.

Don’t mistake the native Eastern columbine for a delicate wildflower. These early spring bloomers can be found growing in some harsh areas, even out of granite boulders in my front yard or on cliff edges.

Native wildflowers that combine well with columbines

The Eastern columbines looks right at home growing alongside other native woodland plants. Besides the maindenhair ferns, mine also share space with Solomon’s seals, foamflowers and bloodroot where they make an attractive early-spring combination with other woodland natives.

Our native Columbines can also look stunning growing in large swaths all on their own or in large garden borders as a middle-height plant where the flowers growing atop the plants provide an almost ethereal feeling.

The columbines and maidenhair ferns both like moist, well-drained sandy, limestone-based soil. If the columbines are planted in too rich garden soil, don’t be surprised if they put on excessive vegetative growth with weak stems. Instead, plants in sandy-type soils will prosper and grow in a more tight, compact form, surviving for many years. They prefer partly-shaded woodland habitat with calcareous soils that are not too rich. A single plant, while in bloom, can put out a large number of flowers. Columbines will naturalize under the right growing conditions and in a woodland or native plant garden.

Native Eastern Columbine in the garden mixed with ferns, epimediums and sedum.

The Eastern red Columbines, also knows as the wild red columbine, or Canadian columbine, is a relatively low maintenance plant that is actually in the buttercup family (Ranunculaceae). Spent flower stalks can be clipped off to tidy up the plant, but don’t cut the plant back to the ground in case it is being used by host larvae.

Columbines can be attacked by leaf miners that leave serpentine trails in the leaves. They are generally harmless to the native plants.

In the wild, native columbines can be found in open woodlands and rocky areas throughout North America. In Canada they stretch from Nova Scotia to Saskatchewan in zones 2-9. It can also be found through much of the eastern United States.

Because these perennial plants, which grow 20 to 30 inches high, are self propagating, my original planting years ago continues to self seed in the same general vicinity where they were originally planted. More native columbines, were planted last year in a shaded area of our back wildflower garden.

Backlit columbine in spring.

Native columbines, know as the Eastern Red Columbine (Aquilega canadensis L.), bloom from April to July in rocky open woods and slopes, and provide an early nectar source for hummingbirds. The flowers are actually a critical food source for returning ruby-throated hummingbirds in spring where they tend to bloom for about a month beginning in May or June depending on weather conditions.

The Eastern Columbine can grow up to 4 ft. tall but don’t be surprised if yours stay much more compact. You can expect the plants to be more in the 6-12 inch zone if grown in shady woodland consditions in average soil.

The showy, nodding red and yellow flowers have five hollow spurs that point upward and contain nectar that is particularly attractive to hummingbirds and other long-tongued insects. Because the flowers point downward, hummingbirds and insects including bees, butterflies and hawk moths have to come up from below the flowers to obtain the nectar.

Finches and buntings are known to consume the small, shiny black seeds that are contained in five pod-shaped follicles after the bloom period.

The columbine is larval host to the Columbine Duskywing skipper found in Southern Ontario and throughout the Eastern United States. The female skipper deposits eggs under the leaves of the native columbine where tiny caterpillars feed on them until they emerge as the small dark brown, nondescript skippers.

I have found that both the deer and rabbits leave these native plants alone in our zone 6-7 garden. In warmer areas, where the plants are considered evergreen, this may not hold true.

The light green to blue-green leaves of the Columbine are divided and subdivided into threes. The foliage is attractive even when not in bloom and turns yellow in fall.

Our native wildflower can be described as an attractive, old-fashioned plant, but it’s not without its accolades. This erect, open herbaceous perennnial plant has received the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit.

That makes it a worthy consideration for a spot in your garden. I grow mine both in the front and backyard.

Don’t mistake the very showy European Columbine (A. vulgaris), with their blue, pink, violet and white short-spurred flowers, with our native variety.

The Canadian Wildlife Federation website also lists the following native columbines for consideration depending on the growing zones where you live.

Sitka columbine (A. formosa)

Native to: southern Yukon, B.C. and swAlta.

Habitat: moist to dry open areas such as streamsides, rocky slopes, woods and meadows at subalpine elevations (moist alpine meadows and mountain meadows)

Appearance: up to about one metre (three feet) tall, nodding red flowers and short spurs

Yellow columbine(A. flavescens)

Native to: B.C. and swAlta.

Habitat: moist meadows, screes/slopes and acid rocky ledges at moderate to high elevations (up to just above timberline and higher than A. formosa)

Appearance: a pale yellow flowering columbine with long spurs, sometimes with a pinkish tinge, blooming from late June to early August. Nodding flowers.

Jones’ columbine(A. jonesii)

Native to: swAlta.

Habitat: subalpine limestone screes and crevices

Appearance: a low-growing plant that reaches five to 12 centimetres tall, with leathery, hairy leaves that bunch together to resemble coral. It has only one or two short-stalked flowers that are a blue and typically face upwards.

Blue columbine (A. brevistyla)

Native to: the Yukon, B.C., Alta., Sask., Man. and central Ont.

Habitat: This boreal forest species of columbine grows in rock crevices, meadows and open woods.

Appearance: blue and white flowers, nodding/upright with short spurs

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

Serviceberry the perfect native tree for the garden

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

Native plants source in Ontario

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

Three of the best Carolinian under story trees (perfect for small yards)

If you are lucky enough to live in the Carolinian forest zone in Ontario or the United States you are able to grow some of the finest understory trees. Here are three of the best understory trees, Redbud, dogwood and Pawpaw. They are small trees perfect for today’s smaller backyards.

Native trees need to be in our gardens

If you are lucky enough to live in the Carolinian zone your garden can be home to a host of exceptional native trees unavailable to many gardeners in colder regions of Canada and the United States.

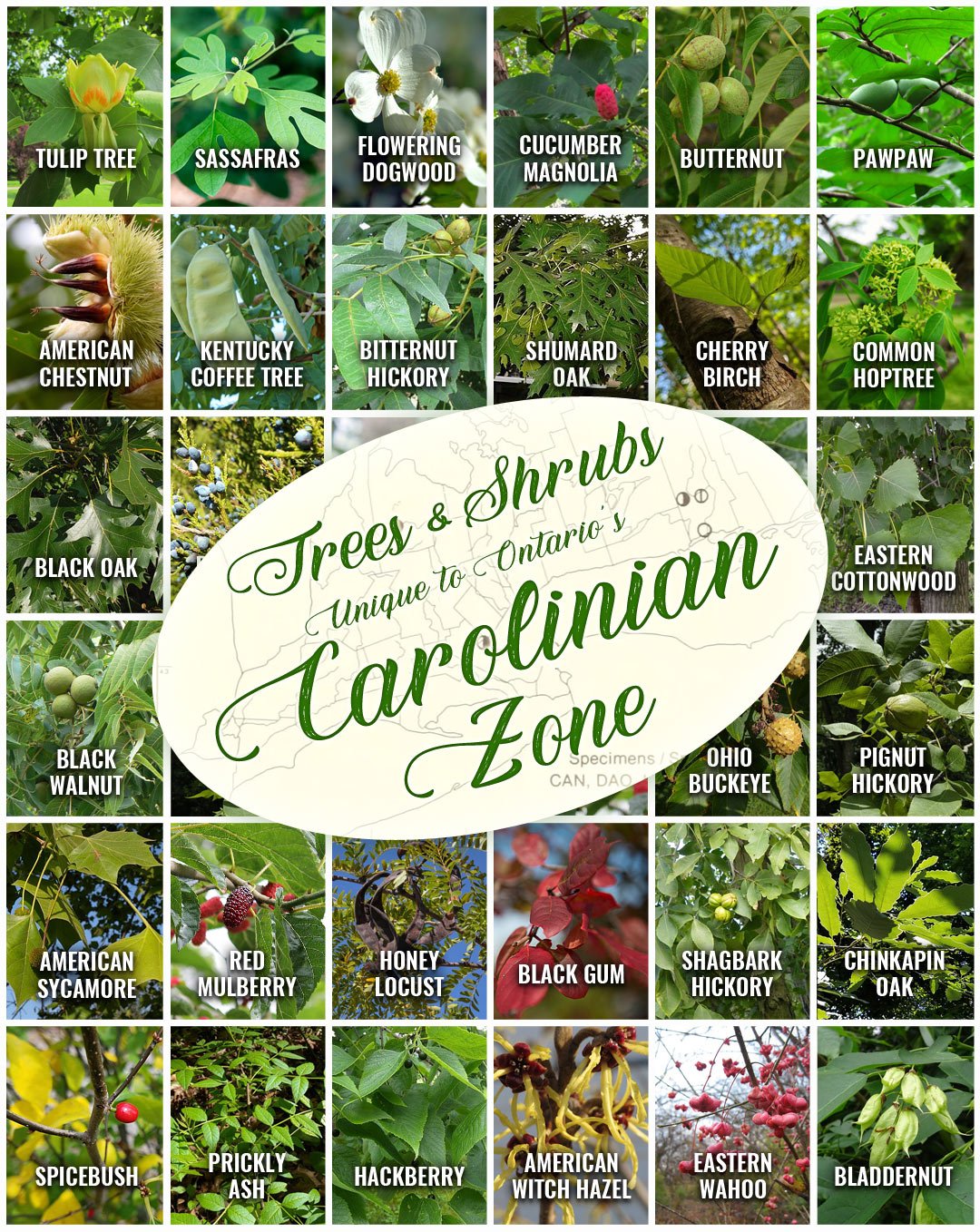

The Carolinian Canada zone in southern Ontario is characterized by the predominance of deciduous trees and actually stretches well into the United States from the Carolinas, through the Virginias, Kentucky, Tennessee, Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, parts of Ohio and New York state to name just a few.

Dogwood among the ferns in the back woodland garden.

In Canada it includes gardening zones 6-7 and shares many of the same animals, trees, flowers and shrubs.

Trees in the Carolinian zone include upper story trees such as oak, hickory, tulip tree and walnut.

But what are the best native understory trees in the Carolinian zone? Carolinian forest understory trees are among the finest and most showy of the available smaller trees, and most would consider the dogwood and redbud to be the showiest. I’m suggesting the Paw Paw to round out the top three for its outstanding fruit production.

(For more on the importance of native plants, trees and shrubs in our gardens, go here.)

These understory trees are ideal for smaller backyards that are common in many of today’s urban and suburban yards.

Let’s take a look at three of the best.

This image illustrates the work of our native carpenter bees who use the Redbud leaves of the Forest Pansy cultivar for their nests. The leaves are just beginning to turn colour for their autumn show.

Redbud (Cercis Canadensis)

The Eastern Redbud, is a hardy understory tree that grows in zones 4-9. It is native to Southern Ontario and is found throughout most of the United States from Florida through to California.

It grows to about 30 feet high with a spread of 35 feet and is available both as a single-stem tree or a multi-stem tree. It has a rounded canopy and tolerates clay soil and the presence of Black Walnut.

My experience is that deer primarily leave the tree alone and outside information seems to back up my findings. So if you are in deer country, put this tree on your list. It’s always a good idea, however, to buy them large enough that deer cannot reach the upper part of the tree.

Redbuds are easily grown in average, medium moisture, in well-drained soils in full sun to part shade.

It is prized for its spectacular early spring bloom of a profusion of tiny pink flowers that lasts for weeks covering the branches prior to the heart-shaped leaves emerge. The result is a stunning early spring display that is really unmatched by any other tree accept maybe the native Florida dogwood which pairs perfectly with the native Redbuds.

One of our Redbuds in full bloom. This is the Forest Pansy that grows beside our shed and provides beautiful magenta/pink blooms against the grey walls of the shed in early spring.

Once the flowers fade the heart-shaped, dark green leaves emerge and remain throughout the summer. The leaves, a favourite for carpenter bees, will eventually put on an impressive fall show of bright, harvest-yellow leaves before falling to the ground. Small, purplish seed pods remain on the tree for a while providing winter interest.

The tree blooms on the previous year’s growth, so it’s best to prune the tree in early spring, after the blooms fade and before it sets bud for next year.

In the wild, the tree is found in woodlands and along creek beds and rivers where it grows as an understory tree in the shade of taller hardwoods and conifers.

In your garden, it can be grown as a specimen or in small groups and woodland margins in a naturalized setting. It is the perfect small tree to grow near a patio or deck.

There are a number of cultivars available including “Appalachian Red” a smaller red flowered variety (zones 4-9), “Ace of Hearts” a more compact form with a dense, domed shaped canopy growing to 12 feet with a 15-foot wide canopy, “Silver cloud” a variegated form of soft green leaves blotched with white that are slightly smaller than the species plants, “Covey” is a small weeping cultivar with a dense umbrella-shaped crown with contorted stems and arching to pendulous branches. Covey is particularly good for small yards or beside patios and decks.

“Forest Pansy” is a purple leaved cultivar. It is one of the most popular cultivars both for its spring show of flowers and its fall show where leaves turn shades of reddish-purple and orange. In cooler climates, the trees foliage retains its rusty/burgundy colour throughout the summer. You can read one of my earlier posts on the Forest Pansy cultivar here.

Dogwood (Cornus Florida)

Often considered the queen of flowering native deciduous trees, there is no arguing that the flowering dogwood (Cornus Florida) deserves a royal welcome in any garden big or small, urban or suburban.

Growing 20-40 feet in height with a delicate horizontal habit of its spreading crown and long-lasting, showy white and pink spring blooms. The 3-inch flower, which are actually primarily large showy bracts, bloom prior to the leaves unfurling giving the tree its spectacular show. Once the spring flowering is complete, the tree’s graceful, horizontal tiered branching habit give way to red fruits that last only as long as birds will allow.

This Carolinian Zone poster was created by Justin Lewis. It is best viewed on a tablet or desktop.

The show does not end after the spring bloom and showy fruit of summer. The scarlet autumn foliage provides the perfect backdrop to the vibrant reds and oranges that often dominate the fall landscape.

In the wild you will find the tree growing near streams, on river banks, in thickets, shaded woods and woodland edges. in shade or part shade. It prefers Rich, well-drained, acidic soil. It can grow in sandy, sandy loam and medium loam that is acid based.

In your garden use it as a specimen but give it room to spread its horizontal, tiered branches as it matures. Its fruit will attract a variety of birds as well as mammals throughout the summer. It will attract a host of butterflies, moths and insects, but is known as the host plant for the Spring Azure caterpillar. The spring azure butterfly is an attractive butterfly with blue undersides marked with black and gray spots.

It is also considered to be especially attractive to native bee species.

It is best pruned in early spring after blooming and efforts should be made to prevent complete drying of soil by mulching the area around the tree. They prefer not to grow in a lawn or surrounded by grass.

Anthracnose disease is an invasive disease, first confirmed in Ontario in 1998 (earlier in the United States) that is threatening the native dogwoods. It is a foliar disease caused by a fungus that can lead to damage and eventual mortality of the tree. It attacks both the Cornus Florida and Pacific dogwood (Cornus nuttalli). At present, there is no cure for the disease.

The emergence of Anthracnose has resulted in many gardeners planting Cornus Kousa varieties which are also beautiful and have many of the same benefits but are not native to the Carolinian zone and flower after the leaves have emerged rather than before.

Don’t let Anthracnose stop you from planting the native tree. They are too beautiful not to have in your garden.

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba)

Imagine going out in your backyard and picking a large piece of fruit (larger than a pear) that tastes as sweet as any mango you’ve tasted.

You might think you’re in some exotic spot, not in southern Ontario or parts of Eastern United States. But you would be wrong.

The Pawpaw tree is not common any longer but it’s making a real resurgence as ecological and food forest gardeners discover the incredible benefits of growing this native tree with its massive, exotic-tasting fruit.

The understory tree reaches about 20 metres tall, with large 30-centimetre long leaves that hang down adding to the tree’s tropical look. Showy red flowers appear before the leaves emerge followed by the yellow-green fruit that matures in the fall where, if left unpicked, will fall to the ground and provide local wildlife with a feast of delicate-flavoured fruit often described to taste very much like a mango.

Pawpaws prefer moist to wet soils in part to full shade in rich, loam soils.

One of the reasons the Pawpaw may have fell out of favour is it’s unusual flower that has been described as having the smell of rotting meat. In fact, the flowers are actually pollinated by beetles and flies rather than bees.

For this reason, it might be better to plants these trees in a back corner of your yard where you can still enjoy the fruit but not the stench of the spring flowers.

Important links for Carolinian zone information

Carolinian Canada operates an impressive educational website that is a must for anyone looking to gather more information on Carolinian Canada. Click here to visit their site.

In The Zone is an organization aimed at protecting and promoting the Carolinian Forest to gardeners. Click here to visit their site.

Carolinian Forest Wikipedia offers a host of links and information on the Carolinian forest. Click here to check out the site.

Redbud tree many images and a host of information can be found here.

Pawpaw tree images and information can be found here.

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

Serviceberry the perfect native tree for the garden

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

Native plants source in Ontario

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

Bringing Nature Home by Douglas Tellamy

A little Love for the Black-Eyed Susan

Native moss in our gardens

This page contains affiliate links. I try to only endorse products I have either used, have complete confidence in, or have experience with the manufacturer. Thank you for your support.

White pine: Native evergreen that helps birds and wildlife

Our native Eastern White Pine is an elegant, open evergreen that deserves a place in more gardens. The tree’s beauty is evident in its early stages. The fast-growing tree eventually becomes a stately, flat-topped tree that has captured artists for years. It is also an important tree to attract wildlife to our backyards.

White pine is showstopper in Carolinian forest

The eastern white pine just might be the single greatest tree for the woodland and wildlife garden.

There, I said it. And I’ll stand by it too.

In fact, our native pine tree (Pinus Strobus) is not only beautiful in every stage of life, it also provides nesting habitat, food and shelter for numerous backyard birds. This alone would make it a standout on most lists, but add the fact it looks as good in spring, summer and fall as it does in the coldest of winters, when neighbouring trees are stripped of their leaves, and you’ve got yourself a real winner.

The Eastern White Pine is the only pine species that is native to the Carolinian Zone of Southern Ontario.

(For more on the importance of growing native trees, plants and shrubs in our gardens, go to my article here.)

It grows in zones 2 to 7 making it the perfect addition to many Canadian and American woodland and wildlife gardens looking for a tree with four-season interest. In the forests of Eastern Canada, the white pine stands above the rest growing taller than any other tree.

It’s too bad not enough gardeners celebrate our native pine and Ontario’s Provincial tree enough to plant it every chance they get.

How close should White Pine be spaced apart?

I’m a firm believer that too many plant nurseries and even experts recommend planting trees and shrubs too far apart in order to give them room to grow. That’s fine if you want to treat the tree or plant as a specimen, but if you are looking for a more full or dense planting closer to a more natural look, ignore these recommendations and plant a little closer.

White Pine are recommended to be planted about 6-feet apart in all directions. That’s perfectly fine, but if you are looking to use them more as a hedge or screen, consider planting them maybe 4 feet apart knowing that they will be growing together in a few years.

The elegance of the Eastern White Pine is evident here with its feathery, blue-green needle clusters and pine cones.

Quick Fact: The University of Guelph Arboretum’s Century Pine Collection is made up of pines that were planted in 1907 and is likely the oldest pine plantation in Canada.

A trip to the local tree nursery often highlights a host of ornamental varieties of our native pine, but few, if any, species examples. (See a partial list of ornamental varieties at end of article)

I’m not sure why so many gardeners often choose a more dense-looking tree like the blue spruce rather than the open, airy feel of a young eastern white pine.

Gardeners may also hesitate to plant the fast-growing tree that typically grows 50 to 80 feet in cultivation, but will grow to between 100-150 feet tall in the wild, with the record holder coming in at 200 ft tall.

So it goes without saying that the white pine is best suited for landscapes with ample space. Don’t let that stop you from squeezing one into your backyard landscape. The size of the trees can be managed somewhat with regular pruning.

I remember my first real introduction to the white pine. I was aware of its elegant branches from my many hikes in local woods and travels to Northern Ontario where the tree often dominates the landscape. In those days, however, I was more concerned with getting photos of the wildlife than admiring the trees. If there was not a bear sitting in the branches, I was not really interested in it.

However, they certainly left an impression on me. To this day, the trees are a vivid reminder of many memorable moments spent wandering Algonquin Park in search of moose, deer, beaver and anything else that would present itself to my camera.

It’s not hard to understand why the Eastern White Pine is a favourite spot for large birds like owls, hawks and eagles to roost in during the day.

It wasn’t until I began to acquire an appreciation for plants, trees and natural landscaping that I really noticed the beauty of the eastern white pine.

A landscaper shared his love for the tree with me during a tour of some of his projects. I remember how he used several of the trees packed close to one another to form a feathery background for a small waterfalls and pond. The trees were pruned to thicken them up and perfectly screened a nearby wooden privacy fence.

The scene, in the middle of a typical, small suburban backyard, took me right back to my days of hiking in northern Ontario.

It also taught me that using large trees on small lots and pruning them to create the shape and size you are after can turn a basic backyard into a woodland retreat one would expect in the heart of northern Ontario or New York’s Adirondacks.

His pruning techniques showed me that there is also a simple solution to the rather open white pines that many gardeners shy away from purchasing. By simply nipping off a third of the candle growth in spring, before they open, the tree will thicken up over time and provide an elegant, blue-green coniferous tree that is equally at home as a specimen in your garden as it is being used in numbers to form a screen or hedge.

A close-up of the tree’s pine cone.

Five White Pine facts

• The Eastern White Pine is a long-lived species that can live up to 200 years or more.

• The tallest tree has been recorded at 200 feet high, but most mature trees growing in the wild can reach 150 ft high and more than three feet in diameter.

• The trees have long been sough out as a traditional Christmas tree, prized for their conical shape and soft, feathery needles.

• Pine needle tea has a pleasant taste and smell and is rich in vitamin C (5 times the concentration of vitamin C found in lemons. Vitamin C is an immune system booster which means the tea can help battle illness and infections.

• Take a handful of pine needles and let them soak in boiling water on the stove. The aroma will add a nice pine smell in the house. Perfect for any time but especially around the Christmas season.

How important are the trees to wildlife?

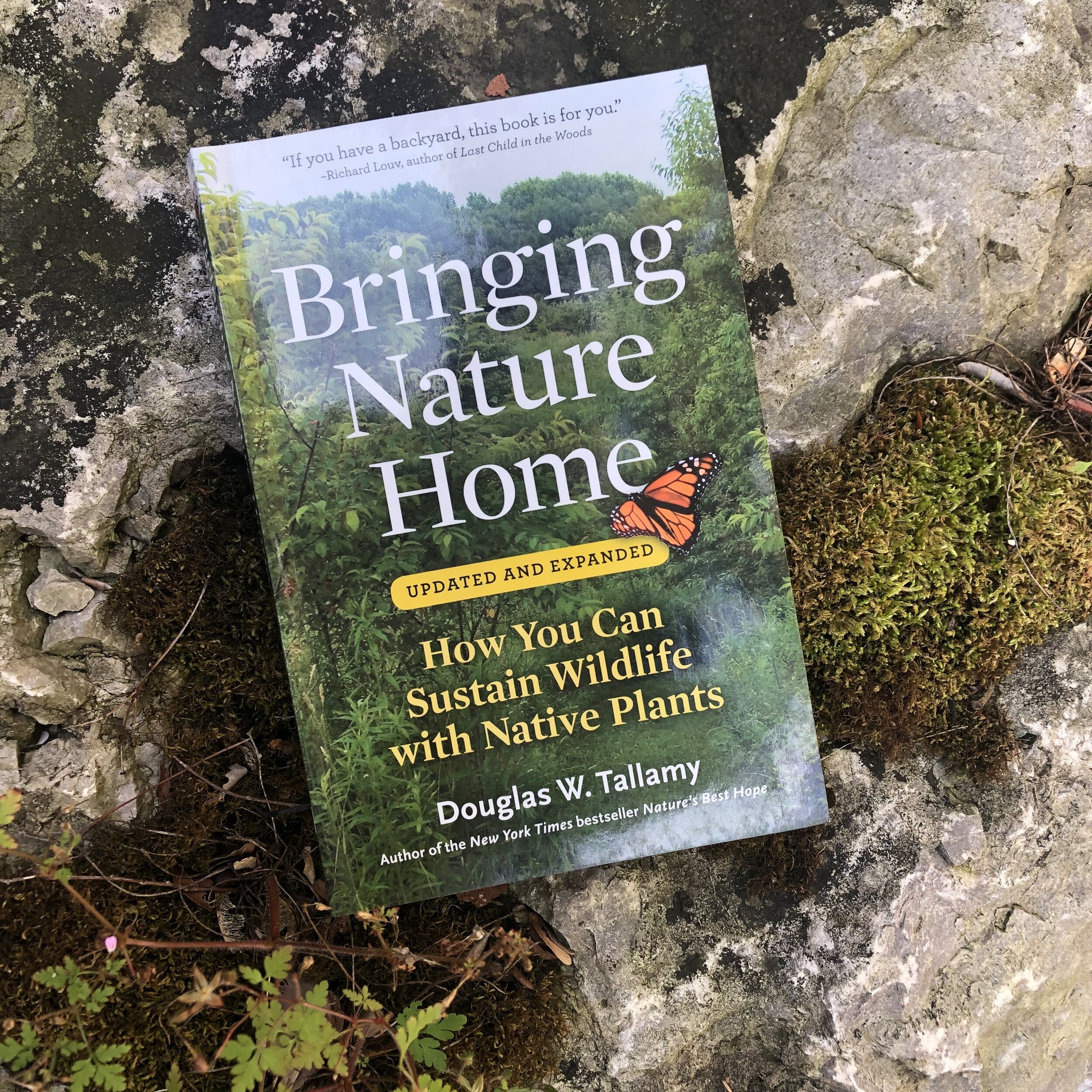

Just how important is the white pine to our gardens and its wildlife? Doug Tallamy, chairman of the department of entomology and wildlife ecology at the University of Delaware, and author of Bringing Nature Home and The Living Landscape, considers the white pine one of the best native trees for providing food, nuts and insects for a host of wildlife.

His hypothesis for the gardener’s lack of enthusiasm toward the white pine is the tendency for the tree to lose its main leader to ice storms when grown in the open as a specimen. The result is a spreading flat-topped tree.

Anyone familiar with the Canadian Group of Seven artists, however, know full-well that it is this flat-topped look that inspired many of their greatest landscape paintings including A.J. Casson’s 1957 painting entitled “White Pine.” A perfect illustration of how the pines take on their elegant flat-topped look as they age. This link shows the painting.

Quick Fact: This tall and stately conifer was once a favourite for ship masts as well as furniture building.

“Every creature is better alive than dead, men and moose and pine trees, and he who understands it aright will rather preserve its life than destroy it.”

If grown in a sheltered forest setting with rich soils, the eastern white pine can become huge with large straight trunks. Although it often goes unnoticed in the woodland setting, a recent drive through the forest around our home revealed a stunning number of natural white pine in various stages on life.

It is the host plant for the Eastern Pine Elfin and used extensively by the imperial moth. The Pine Elfin is a rather drab brownish butterfly, which is found in most of the eastern U.S. and in Canada from the Atlantic provinces through Ontario, southern Manitoba, central Saskatchewan, and into Northern Alberta.

The imperial moth is one of the largest and most impressive in its range. Although more common in the southern United States it can be found as far north and the southern Great Lakes.

Pine needles in general are favourites of 203 species of moth and butterfly larvae.

The Audubon Society reports that seeds found within the pine cones are food for up to forty species of birds (including blue jays, brown thrashers, cardinals, chickadees, nuthatches, grosbeaks, juncos and woodpeckers) as well as red fox and gray squirrels, chipmunks, mice and voles. Expect to wait between 5-10 years for the brown cones (4-8 inches long) to be produced on the tree.

In fact, the seeds are an important food source for crossbills which will even migrate from Canada to the United States during some winters in search of white pine seeds.

Pines, including the white pine, are also home to sawfly caterpillars, a staple of many birds in early spring looking to feed their young.

Is there any doubt that you need a couple of these white pines for your backyard?

If so, consider that the soft, feathery foliage of the White Pine is an excellent source of nesting material. In fact, when setting up a bluebird box it is often recommended to use a handful of white pine needles in the boxes to attract a nesting pair.

The white pine offers refuge for birds during cold winds and snowstorms, as well as relief from extreme sun and heat during summer months.

Owls, hawks and eagles often perch in the trees to take advantage of the views the open branches of mature specimens provide. Eagles are known to prefer a mature, flat-topped pine for nesting.

Botanical Name: Pinus strobus

Common Names: Eastern white pine

Plant Type: Needled evergreen tree

Mature Size: 50 to 80 feet tall, 20- to 40-foot spread

Sun Exposure: Full sun to part shade

Soil Type: Medium-moisture, well-drained soil

Soil pH: 5.5 to 6.5 (acidic)

Hardiness Zones :2 to 7 (USDA)

Native To: Southeastern Canada, eastern U.S.

Mourning doves, purple finches and robins also use the open branches as favourite nesting sites.

Although the white pine is an excellent ornamental tree, it requires favourable growing conditions to thrive. Grow it in fertile, moist, slightly acidic, well-drained soil in full sun. They will tolerate some shade, but will not do well in hot, dry, infertile, compacted, alkaline or heavy clay soils.

What native plants grow beneath a white pine?

If you have ever looked under a white pine, you would be hard pressed not to notice the abundance of dried needles that form a thick mulch. The needles not only form a mulch, they also help to create a somewhat more acid environment under the tree. This together with a lack of water adds to the difficulty of growing plants under the pine.

Consider using these plants under your tree: Bearberry, Wild Ginger, Columbine, White Woodland Aster, Heart Leaved Aster, Wild Geranium, Woodland Sunflower, Mayapple, Jacob’s Ladder, Solomon’s Plume, Starry Solomon’s, Goldenrod and Bellwort.

Native ferns that can be used include: Maidenhair Fern, Lady Fern, Oak Fern and Royal Fern

Road salt and other elements that can harm white pines

Don’t plant your pine close to busy streets. They are susceptible to damage by road salt as well as air pollution and drying winds. The branches can suffer severe damage in ice storms and heavy snow.

If planted in less than ideal conditions, young and recently planted trees can suffer from white pine decline, characterized by a decline in needles until they have only small clusters of stunted needles at their branch ends. This is a signal to move the tree to more ideal locations in the garden.

Other problems include white pine root decline, blister rust disease (caused by gooseberry or wild currant bushes growing nearby), white pine weevil, European pine shoot beetle and European pine shoot moth.

Don’t let any of these potential problems stop you from planting this native.

Nothing, not even the white pine, is perfect.

The pine trees seen here are being used as a screen on this larger rural property to block the view of the house.

White Pine cultivars

Blue Shag – is a dwarf, dense, eastern white pine ideal for use in rock gardens, as a foundation planting or in a shrub border.

Fastigiata – is a small to medium-sized cultivar with a narrow, upright, columnar habit. Grows 30 to 40 feet tall, but only 10 feet wide. The tree’s shape broadens with age.

Hillside Winter Gold – is a fast growing upright, full-sized cultivar with an open, pyramidal habit. Typically grows 12 to 15 feet over the first ten years, eventually reaching 30 to 70 feet tall.

Horsford – a dwarf cultivar that has a dense, rounded growth pattern and grows slowly (3 inches per year) to form a miniature mound of foliage to 1 foot tall. Works well as an accent in the rock garden.

Macopin – is a broad upright, irregular, compact, shrubby form which grows at an intermediate rate (6 to 12 inches per year) to 3 feet tall by 3 feet wide (sometimes larger).

Pendula – is a semi-dwarf cultivar with weeping, trailing branches that may touch the ground. It typically grows to 6 to 15 feet tall with a larger spread.

Pinus strobus (Nana Group) – is used by many nurseries as a catchall term for describing a group of compact, shrubby, mounded, irregularly branched, spreading, dwarf forms of eastern white pine. These plants are very slow growing, often reaching only 2 feet tall after 10 years. They eventually mature to 3 feet tall by 4 feet wide, but less frequently may reach 4 to 7 feet in height and 6 to 10 feet in width. Silvery, blue/green needles are soft to the touch.

Loui – Boasts a golden-green colour years round and comes highly recommended from a reader.

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

Serviceberry the perfect native tree for the garden

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

Native plants source in Ontario

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

As an affiliate marketer with Amazon or other marketing companies, I earn money from qualifying purchases.

Seven Viburnums: Top shrubs to attract birds to your garden

Building up the number of viburnums in your garden design is a great way to not only beautify your backyard but create a garden that is attractive to a wide variety of birds. Viburnums provide an abundance of flowers in spring, attract pollinators, insects and caterpillars throughout the summer, outstanding leaf colour in fall and an abundance of berries in fall lasting well into the winter.

High bush Cranberry is both beautiful and attracts birds

There is no question that shrubs in the Viburnum family are ideal choices for bird and wildlife lovers. But it’s important to note that they’re not just for the birds.

Gardeners will appreciate our native Viburnums as much in the spring garden with their impressive display of white flowers that attract an array of pollinators, as they will in the fall when their berries are in full bloom.

The one thing you should remember, however, is that you can’t have a bird garden without Nannyberry, Witherod, Hobblebush or High bush Cranberry.

In fact, woodland gardeners looking to attract an array of colourful birds to their backyards should consider the Viburnums as the stalwarts of their shrub borders.

While I get great enjoyment from my bird feeding stations, providing natural food sources to our feathered friends is always the goal we should aspire to in our gardens. I have written a comprehensive post on feeding birds naturally. You can read about it here.

The large family of shrubs provides birds with most of what they need, from nesting and shelter areas, to insects and a plethora of berries.

A Hermit Thrush eyes the fruits of the High bush Cranberry in the wooodland garden.

In zone 5, gardeners can expect fruit to be on display from as early as June through to January and beyond.

Your local high-end garden centre should carry a good selection of viburnums (see link at bottom of post) to choose from, just make sure that they are not hybrids that no longer provide resources for our backyard wildlife.

During the spring and summer, Viburnums are host to a selection of leopidoptera (butterflies and moths) at the caterpillar phases including species such as the Holly Blue Butterfly (Celastrina argiolus), the Hummingbird Clearwing moth (often mistaken for a hummingbird) and the silk and sphinx moths.

The caterpillars are an extra bonus providing important early food sources for birds feeding their young at the nest.

The flowers of the viburnum eventually give way to abundant array of colourful fruits that our backyard birds depend on to get them through the fall and winter.

For woodland gardeners, the range of colours the leaves of our native Viburnums turn as winter approaches is a pure visual treat.

A woodland of deciduous trees will provide the best shelter for them and early spring is the best time to plant them, just when the ground is thawing and the large buds have not yet opened. Plant them in time to enjoy the large flowers before they emerge in spring.

Although there are more than one hundred kinds of Viburnum throughout the world, in North America the major plants are the Hobblebush (one of the first fruit-bearing shrubs to bloom, with berries available all summer long in the woodland understorey.) The somewhat similar Nannyberry and Witherod, are often found in the wild growing in open ground, both with blue-back fruit that is eaten during the October migrations; and the High bush Cranberry, which keeps its fruit until the following spring.

Viburnum with berries in it’s vivid fall colours.

What birds do Viburnums attract?

Viburnums are known to attract Bluebirds, Cardinals, Robins, Cedar Waxwings, Purple finches, Waxwings, Thrushes and Evening grosbeaks and Grouse. The shrubs are found through the northeast United States as far south as subtropical soils, and westward until the mountains block further progress.

The inland North American continent favours a variety of Viburnum shrubs, the best known being the American High bush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum ) The high bush cranberry is native to every province in Canada in wet areas such as in thickets along shorelines, swamps and forest edges. In the United States, it is found from Pennsylvania to Wyoming.

The plant resists disease and severe pruning, and transplants well. Caring for it is relatively easy. They are susceptible to the larvae of the viburnum leaf beetle, which feed on its leaves. These European beetles can slow the growth of the bushes and even kill them if left unchecked. Clipping off affected branches and disposing of them usually solves the problem.

The plant’s soft green foliage changes to a warm brick red with the first fall frosts. Because the fruit stays on the branch much later than that of other shrubs it adds a bright red highlight to what is otherwise often a rather stark view of our woodland gardens.

The berries soon become a very important source of food for either our winter birds and late migrants, or the early spring migrants looking for critical sustenance at a key time. Don’t be surprised to see Pine Grosbeaks feasting among its branches.